Taiwan ranked 52nd out of 61 countries in the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI)—an annual assessment that evaluates and compares national climate change mitigation efforts—at the end of 2016. Nearly a decade later, Taiwan remained near the bottom, placing 60th out of 67 countries in the 2025 CCPI.

This sustained poor performance raises important questions about the effectiveness of former President Tsai Ing-wen’s (蔡英文) climate policies during her tenure in office from 2016 to 2024. It also prompts an analysis of the obstacles to Taiwan’s energy transition facing current President Lai Ching-te (賴清德). These questions include: 1) How effectively has the Republic of China (ROC) government supported the country’s move to renewable energy since 2016? And 2) How can the Lai Administration address the remaining unresolved challenges over the next three years?

Evaluation of the Tsai Administration’s Energy Policy

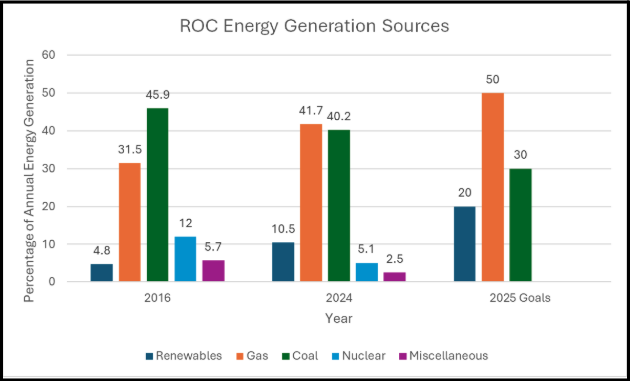

In 2018, the Tsai Administration announced Taiwan’s renewable energy goal for 2025, aiming to source 20 percent of its energy from renewables, 30 percent from coal, and 50 percent from low-carbon natural gas—an objective commonly known as Taiwan’s “20-30-50 formula.” Tsai built upon this commitment in April 2021 when she restated that her administration’s long-term renewable energy policy was to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. In March 2022, the ROC government released its action plan in a report titled Taiwan’s Pathway to Net-Zero Emissions in 2050.

The Tsai Administration introduced a series of legal reforms to pursue this renewable energy goal. It amended the Electricity Act (電業法) three times as well as the Greenhouse Gas Reduction and Management Act (溫室氣體減量及管理法), now called the Climate Change Response Act (氣候變遷因應法). The Electricity Act amendments allowed direct sales of green energy to users as part of the government’s efforts to “promote [the] liberalization of the green energy market.” This regulatory framework allowed major transnational companies like Google to purchase renewable energy for their business operations, such as data centers, while still investing in the Taiwanese economy. The amending of the Greenhouse Gas Reduction and Management Act created a carbon pricing system with both levies and fees. This change provided additional financial incentives across the energy production and usage supply chain to minimize the use of carbon-based energy sources in favor of green energy alternatives. Taken together, the amendments to the Electricity Act and the Greenhouse Gas Reduction and Management Act offered financial incentives for businesses to use green energy, while penalizing carbon-heavy options and establishing a conducive regulatory environment.

However, despite creating a favorable climate for renewable energy, the Tsai Administration failed to achieve its 20-30-50 formula by the end of its term in office. The graph below demonstrates that a lack of renewable energy and overreliance on coal throughout Tsai’s tenure contributed to this unsatisfactory outcome.

Figure 1: Graph showing changes in Taiwan’s actual energy generation sources between 2016 and 2024, compared to the Tsai Administration’s targeted 20-30-50 formula for 2025. (Figure source: ROC Ministry of Economic Affairs, Energy Administration)

Reasons for Failure

The Tsai Administration fell short of its energy objectives for two primary reasons: insufficient renewable energy generation capacity and growing domestic energy needs. The Tsai-led Democratic Progressive Party (DPP, 民進黨) controlled the executive and unicameral legislative branches throughout her tenure as president. As described above, the DPP used this power to amend the Electricity Act and the Climate Change Response Act. Despite these successes, Taiwan’s renewable energy generation capacity did not improve quickly enough to meet stated goals (see Figure 1). Additionally, Taiwan’s energy demand growth also detracted from the Tsai Administration’s ability to reach its energy goals. Taiwan has averaged 0.41 percent growth in domestic energy consumption every year since 2003. In 2024, Taiwan’s total energy demand was 3.35 percent higher than it was in 2016, when Tsai first assumed office. While this increase may appear modest, growing energy demand has nevertheless forced an even greater emphasis on the use of renewables to meet the Tsai Administration’s energy objectives. This reduced generation capacity, combined with rising energy demand, has raised pressure on existing efforts to meet the government’s energy policy priorities.

Two secondary reasons that the Tsai Administration failed to reach its stated energy objectives were limited foreign investment and Taiwan’s exclusion from international institutions. Taiwan needs to double its 2024 renewable energy generation capacity to reach its 20 percent renewables goal by 2025, as demonstrated by the graph above. One possible solution is to construct more wind farms. Of the 370 wind farm sites that the Taiwanese government is considering for construction, the majority could be expected to return a profit if optimally developed. Attracting higher levels of foreign investment to offset the costs of wind site development could be one way to address this issue.

In addition to foreign investment and energy supply concerns, Taiwan’s diplomatic isolation from international energy institutions has hindered its ability to transition more effectively to renewable energy. As analysts Evan Feigenbaum and Jen-yi Hou (侯仁義) have noted, Taiwan is not a member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and therefore is not associated with the International Energy Agency (IEA). Moreover, the IEA hosts the Clean Energy Ministerial Secretariat and Energy Efficiency Hub, a platform for global collaboration on data-sharing and technological development initiatives. The inability of Taiwan to benefit from this forum—once again due to the PRC’s opposition to Taiwan’s participation in prominent multilateral organizations on grounds of the “One-China Principle”—hinders its pursuit of the 20-30-50 objective.

Lessons for the Lai Administration

The Lai Administration inherited this set of policy successes and challenges upon taking office in May 2024. Lai faces two potential major energy policy issues in the remainder of his tenure: rising electricity demand and political friction with the Kuomintang (KMT, 國民黨) over the role of nuclear power.

Taiwan’s electricity demand is set to grow much more quickly over the coming decade than the past twenty-year average of 0.41 percent annual growth. The Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA, 經濟部) predicts that the rise of artificial intelligence-related technologies that use a large quantity of energy, such as data centers, will drive a 2.8 percent increase in energy consumption every year through 2033. This means that the Lai Administration will face even more acute pressures to meet the ROC’s renewable energy objectives compared to the Tsai Administration.

However, the DPP no longer controls the legislative branch, as it did during the Tsai Administration. The KMT has allied with the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP, 民眾黨) to control the Legislative Yuan (立法院) since the start of Lai’s presidency. The failure of the summer 2025 DPP-aligned civic group electoral recall campaigns to remove a single KMT legislator means that Lai must still reckon with a KMT- and TPP-aligned legislative branch when advancing any legislation. While the KMT broadly accepts the need to transition to renewable energy, it embraced the view that nuclear power was a necessary component of Taiwan’s energy supply in the 2024 presidential election. As the anti-nuclear movement is a core facet of the DPP’s political charter, the opposing views of the KMT and DPP on nuclear power may lead to increased gridlock on energy policy.

Lai should learn from the Tsai Administration and prepare to generate joint public-private investment in constructing renewable energy generation and storage capabilities. In their paper, Feigenbaum and Hou propose two options for Taiwan’s energy storage. First, Taiwan can look toward megapack solutions that focus on providing storage for commercial renewable energy sources to meet periods of peak electrical demand. Successful examples around the world include South Australia’s Hornsdale Power Reserve and California’s Moss Landing project. Second, Taiwan could draw inspiration from Australia by adopting the concept of virtual batteries. This approach allows individuals to lease small portions of their battery storage to the grid in times of intensified energy demand. Expanding storage capacity also helps mitigate the volatility of renewable energy by, for example, enabling the storage of excess energy produced on windy days for use during periods of low wind activity. These two approaches offer practical opportunities for the Lai Administration to collaborate with the private sector along the path to renewable energy transition.

The main point: The Tsai Administration set an ambitious “20-30-50 formula” for Taiwan’s energy sector by 2025. Yet, upon leaving office in 2024, it had not positioned Taiwan to achieve this objective in the year ahead, primarily due to a lack of renewable energy generation capacity and intensifying energy demand. The Lai Administration now faces a challenging political environment concerning two potential major energy policy issues: rising electricity demand and political friction with the KMT over the role of nuclear power. Lai should learn from the Tsai Administration’s energy policy failures and prepare to generate joint public-private investment in constructing renewable energy generation and storage capabilities.