There are at least two well-documented trends that inform Taiwan’s demographic problems. First, the country is aging rapidly. The proportion of the population aged 65 and above is forecast to rise from 12 percent in 2015 to 40 percent in 2060. Second, the overall population is forecast to shrink. By 2060, the overall population will reduce by 5.3 million. The challenges that come with this dual-natured problem are numerous, but one of the most significant factors contributing to the demographic challenges in Taiwan is its low birthrate.

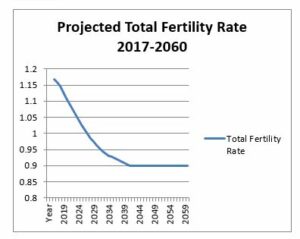

Taiwan made global headlines when its total fertility rate hit an all-time low of 0.89 in 2010. The total fertility rate is the measure of the average number of births per women in a country. In recent years that number has increased to 1.17, but serious challenges remain. Taiwan currently has the third lowest fertility rate in the world. If the situation does not improve, the projected overall fertility rate will drop back down to 0.9 by 2060 (see Figure 1). This is an unsustainable drop that could have potentially devastating economic and security implications for Taiwan.

A low birthrate leads to population aging, which challenges the healthcare and pension systems and places a burden of care on young people. Population decline slows down the economy and leads to a reduction in national wealth. It also puts a huge strain on the education system. Former President of Taiwan, Ma Ying-jeou, noted the importance of this problem when he said that “the low birthrate is a serious national security threat.”

The main explanations for sustained low fertility rates in Taiwan are the high cost of childbearing (cost of living and educational expenses) and the social cost to women, who have to balance a career and family. In the 1970s, an effective family planning program, focusing primarily on increasing the use of contraception, was influential in the gradual fertility decline in Taiwan.[1] More recently, there has been a demographic trend towards later childbirth and the postponement of marriage due to high levels of female tertiary education, greater female workforce participation, and more financial independence for women. But these reasons mirror the situation in much of the developed world. So why is the situation in Taiwan so much worse than in other countries?

A number of explanations have been offered for this phenomenon. Basten and Verropoulou suggest that “working hours, limited welfare provision, [and] the burden of caring for aged parents (and in-laws)” are important issues affecting the birthrate, and are issues that are specific to Taiwan. In addition to this, the changing nature of the labor market in Taiwan has caused a stark generational shift in working patterns. Taiwan has experienced a steady and continuous decline in the agricultural and manufacturing sectors, alongside continued growth in the commerce and financial services sectors. This shift, alongside the percentage of tertiary-educated women now exceeding that of men, means that more women are working in the formal service sector than ever in Taiwan. Yu explains that highly educated, young Taiwanese women are being forced to choose between career and family in the formal labor market, whereas previous generations were able to balance families with informal work.[2]

The cost of living, and availability of childcare in Taiwan is also often cited as a serious challenge for couples wanting to have children. It has also been suggested that the traditional nature of Taiwanese society does not encourage women to have children outside of marriage. In France, as is common among European countries, 53 percent of births occur outside of marriage—in Taiwan this number is just 4 percent.

The Taiwanese government is aware of this problem. In her presidency’s inaugural address, President Tsai Ing-wen spoke to this, suggesting that, “our birthrate remains low, while a sound childcare system seems a distant prospect.” Speaking at an International Women’s Day event in March 2017, President Tsai said, “supporting and removing barriers to female employment is an important government policy.”

National measures to encourage fertility and childbearing exist in Taiwan. These range from childcare subsidies and improvements in reproductive care, to partially free education for preschoolers and maternity benefits. The incentives offered by the Taiwanese government include a monthly subsidy of NT $2,500 to NT $4,000 (US $81 – US $130) for families raising a child, a subsidy of NT $2,000 (US $65) each month for child minding and free tuition for children aged 5. Families can also obtain benefits from their local governments. President Tsai is working to instill concepts of gender equality in Taiwan’s policy. Steps have also been taken to amend the Gender Equality in Employment Act that requires companies with over 100 employees to set up childcare centers. The government is additionally aiming to provide women with subsidies, job training and employment advice to help them return to the workforce after a period of maternity leave.

Much discussion on this topic suggests that societal change is also needed. President Tsai has said that raising children is not just the responsibility of parents, but needs the support of society. Frejka et al. also explain that sufficient attention is not being paid to generating broad social change that is supportive of parenting. Fertility patterns will not change unless child- and family-friendly environments are fostered, including the equal participation of men and women in the household, and improved attitudes of employers towards parental leave. The labor participation rate among married people in Taiwan is illustrative of the enduring social divide—labor participation for married men is 70 percent, but only 49 percent for women.

Studies looking at fertility intentions in Taiwan have found that two children is the ideal number of children that Taiwanese women would like to bear. It has been argued that Taiwan’s fertility preference rate can be used to understand potential future directions of fertility. This paints a positive picture for the future, but requires the right governmental support and societal change.

If the Tsai government can adjust policy to better encourage childbirth and initiate a level of societal change, Taiwan can increase its fertility rate from its current downward projection towards 0.9. It is a good sign that President Tsai has publicly stated the need for societal change, but the course towards this will be long and laborious.

The main point: Fertility and demography are inextricably linked. Sufficient attention is not being devoted in Taiwan to developing social change that leads to increased fertility.

[1] G. Cernada, T.H. Sun, M.C. Chang, and J.F. Tsai, “Taiwan’s Population and Family Planning Efforts: An Historical Perspective,” International Quarterly of Community Health Education 27, no. 2 (2007): 99-120, doi: https://doi.org/10.2190/IQ.27.2.b.

[2] Wei-hsin Yu, Gendered Trajectories: Women, Work, and Social Change in Japan and Taiwan (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009), 119, 199.