Eric Chan is a non-resident fellow at the Global Taiwan Institute and a senior airpower strategist for the US Air Force. The views in this article are the author’s own, and are not intended to represent those of his affiliate organizations. Lt. Gen. (Ret.) Wallace “Chip” Gregson is the former Assistant Secretary of Defense, Asian and Pacific Security Affairs (from 2009 until 2011), and a member of the Global Taiwan Institute’s Advisory Board.

The assassination of former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe (安倍 晋三) on July 8, 2022 was a heavy blow for supporters of democratic cooperation against authoritarian coercion. Abe had a long history of promoting greater regional networks to counterbalance the increasing threat from the People’s Republic of China (PRC). For instance, his 2007 speech to the Indian Parliament on the importance of joining the Pacific and Indian Oceans as part of a “broader Asia” was the genesis of the term “Indo-Pacific,” which moved the contextual framework of strategic thought from an Asia centered on China to one including India and Southeast Asia. Such was the power of the term that the CCP directed PRC diplomats to warn countries against the use of the phrase.

Abe’s legacy was not built on terminology alone. As prime minister, he was a champion of the formation of “The Quad,” the loose strategic framework joining the United States, Japan, India, and Australia. In addition, he further transformed Japanese bilateral relationships with India and across Southeast Asia (particularly with Vietnam and the Philippines), deftly weaving values and national interest to counter PRC influence.

What could arguably be his most impressive foreign policy achievement, however, was his transformation of Japan’s relationship toward Taiwan. Given the nature of the PRC threat towards Taiwan, this represented a sea change in how Japan views the region, as well as its own uneasy relationship with the role of military power in national security. Legal reforms during Abe’s administration mean that the Japanese military can now use force in the context of collective self-defense (for instance, a Taiwan contingency) rather than only as a response against direct attack. In the aftermath of Abe’s death, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) coalition has now amassed a significant majority in Japan’s upper house. While popular commentary has focused on the potential for the LDP to revise Japan’s pacifist constitution, the significant amount of political capital and attention that would be required to effect such a largely symbolic change might be more gainfully directed towards expanding Taiwan and Japan defense cooperation. The recent PLA firing of Dongfeng ballistic missiles into Japan’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) as part of its larger encircling coercion operation against Taiwan makes it clear that Taiwan and Japan’s security is now inextricably linked. Thus, defense cooperation should be, as well. This cooperation would assist Taiwan and Japan in deterring PRC aggression, as well as imposing higher costs on the PRC for engaging in gray zone warfare.

In this article, we explore three methods of expanded cooperation: advancing security cooperation via a new Japanese Taiwan Relations Act (TRA), establishing a professional military education exchange system, and coordinating against People’s Liberation Army (PLA) gray zone warfare.

Advancing Security Cooperation via a Japanese TRA

The latest Japanese defense white paper identifies Taiwan as “important for Japan’s security and the stability of the international community.” Even after Abe’s reforms, though, this identification is only useful in the context of policy deterrence related to a Taiwan crisis: the PRC must now consider the prospect of earlier and more proactive Japanese intervention in conjunction with the United States.

Yet, current legal authorities and established government-to-government channels do not effectively address how Japan can work with Taiwan, either bilaterally or with the United States, on a day-to-day basis. A Japanese TRA would provide the legal framework for holistic cooperation in pacing competition: diplomatically and informationally pushing back against the PRC’s efforts to dominate the region; coordinating against PRC economic coercion; and expanding military cooperation and readiness against both gray zone and conventional warfare.

Moreover, a Japanese TRA with policy language modeled after that of the United States (“shall make available to Taiwan such defense articles and defense services in such quantity as may be necessary to enable Taiwan to maintain a sufficient self-defense capacity”) would hold out the prospect of significantly increased military-industrial cooperation. The LDP’s proposal to double Japan’s defense budget over the next five years will mean that the Japanese military will enjoy vastly sped-up and increased defense orders for things like supersonic anti-ship missiles and air defense capability–exactly the same capabilities that Taiwan is interested in. As the proposal also looks to loosen Japanese arms exports restrictions, a Japanese TRA would allow Taiwan to jointly participate in arms orders, taking advantage of volume discounts. This would also allow Taiwan’s defense industry to more openly collaborate with the Japanese defense industry on everything from supply chain construction to research and development. Solidifying the flow of foreign military equipment, as well as further developing Taiwan’s indigenous defense industry, would be an enormous benefit to the development and sustainment of Taiwanese defense capabilities—particularly complex programs like the Indigenous Defense Submarine (IDS, 潛艦國造).

Establishing a Professional Military Education Relationship

When it comes to defense, equipment is important, but human capital is even more critical. Many people think of security cooperation as being primarily focused on foreign military sales, but a much more vital piece of a close defense relationship is composed of people-to-people relationships, education, and training. In a crisis, personal relationships play a critical role in speeding up aid across (and sometimes around) bureaucracies. In the Russia-Ukraine War, the relationships formed between the Ukrainian Air Force and the California National Guard as part of the State Partnership Program were instrumental in three areas: first, the military training itself; second, both sides gained a better understanding of the capabilities that each might be able to offer during a crisis; and third, the personal contacts made during training formed the basis for immediate crisis communications prior to the establishment of more formal cooperation organizations and structures.

Thus, the establishment of a professional military education (PME) relationship across the entire spectrum of a military member’s career would have significant effects for the Taiwan-Japan relationship. Regular engagement—from cadet level, to junior/mid-level officer and non-cimmissioned officer (NCO) exchange courses and training, and finally to the war college level—would create a diversified pool of contacts familiar with the technical and operational details of one another’s respective militaries. It would improve strategic-level assessments of defense capability and intent, allowing for better interoperability if and when the time comes that formal coordination becomes possible. In the long run, it would also create a natural constituency for increased partnership. For instance, the Japan-America Air Force Goodwill Association (JAAGA), comprised of retired Japan Air Self-Defense Forces general officers and colonels—many with experience in the US PME system—represents a powerful constituency for a close US-Japan defense relationship.

Finally, the development of PME relationships would allow both Taiwan and Japan to easily scale up further engagement, from strategic-level discussions between senior officers to operational-level coordination between war planners. This lack of coordination, or even a common operating picture, has allowed the PRC to separately and effectively wage gray zone warfare.

Coordinating Against Gray Zone Warfare

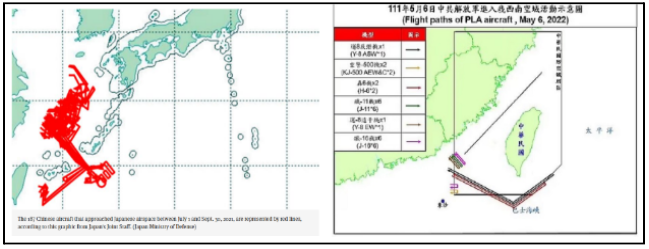

The PLA method for gray zone warfare revolves around the old dictum of divide and conquer. Both Taiwan and Japan suffer from constant incursions by the PLAAF and China Coast Guard, which have dramatically escalated over the last few years.

With a Japanese TRA and a firm training relationship, the next step would be intelligence sharing, which could provide a common operating picture. Such a picture would allow the two militaries to establish priorities for intercepts in the air and on the sea. Against “day-to-day” incursions, this would allow for some level of tandem, unmanned aircraft response to put countervailing pressure on the PLA to divide its attention and preserve combat power.

Against surges of PLA activity, as demonstrated by the aforementioned PLA firing of five ballistic missiles into Japan’s EEZ, but also the missile overflight of Taiwan, multiple unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) flying around Kinmen (金門), as well as large-scale fighter/naval incursions across the Taiwan Strait median line, even more robust coordination would be required. This would mean liaison officers embedded in respective air operations centers for real-time intelligence sharing, analysis, and air response/missile defense deconfliction; the establishment of encrypted communications would allow for crisis management between operational headquarters. This would form the basis for a coherent information network/sensor “kill web,” vastly increasing partner situational awareness and combat capability.

An effective partnership in the gray-zone fight would free up resources and provide an excellent basis for further cooperation in training for the high-end fight. A kill web sensitive to gray zone incursions would also provide improved indications and warning against PLA mobilization for an invasion. Quiet, quadrilateral coordination between the United States, Japan, Taiwan, and Australia could provide multiple venues for operational-level observation or training: in areas such as practicing aircraft deployment under simulated attack, marine corps training for coordinating long-range fires and counter-attacks in littoral areas, or ground force training in beachhead containment given a highly-contested air environment.

In short, Taiwan-Japan coordination to impose costs on the PRC for using gray zone warfare would also strengthen both nations’ ability to win against an all-out invasion.

The PRC has long used bilateral coercion and pressure against both Taiwan and Japan. By exploiting Japan’s pacifist constitution and holding out carrots to the Taiwanese and Japanese business communities, the PRC has consistently been able to paralyze the establishment of a common response to coercion.

Shinzo Abe’s legacy of taking steps to “normalize” Japan while championing outward-looking, values-based engagement, has set the stage for Taiwan and Japan to explore multiple venues for defense cooperation. Full-spectrum cooperation—that is, engagement that addresses both gray zone warfare and the prospect of an all-out invasion—will be critical for maximizing deterrence during this decade of maximum danger from an aggressive, revanchist PRC.

The main point: Shinzo Abe’s transformation of Japanese defense and foreign policy has set the stage for further expansion of Taiwan-Japan defense cooperation. This cooperation will be critical to deterrence against PRC aggression in all its forms.