Cheng-yi Lin is a research fellow at the Institute of European and American Studies, Academia Sinica.

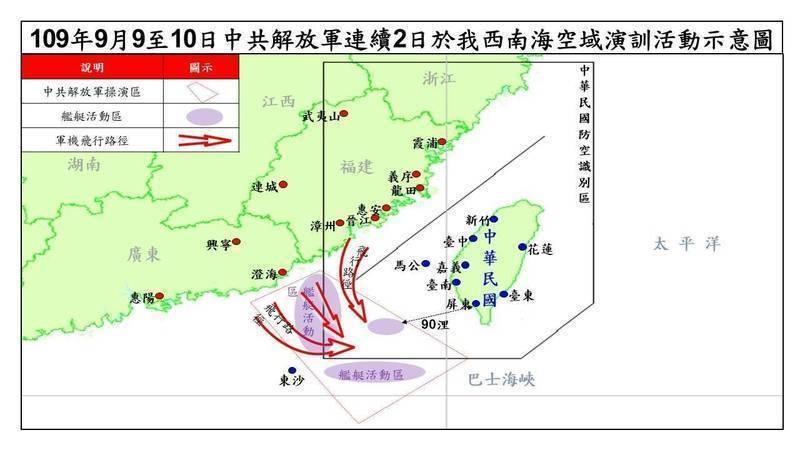

In the vicinity of the Taiwan Strait, the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) first started its “long-distance training over the sea” (遠海長航) in March 2015 and then conducted its first “circumnavigation around the [Taiwan] island” (繞島巡航) following President Tsai Ing-wen’s (蔡英文) inauguration in 2016. The PLA later referred to its air operations as “combat readiness cruises” (戰備警巡) in February 2020, as tensions in the Taiwan Strait were mounting. Since September 2019, the PLA has continued its air intrusions into Taiwan’s southwest Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ), whose southwestern boundaries lie between Taiwan and Dongsha (Pratas, 東沙島) Island, on a nearly daily basis. This article will assess the motivations and implications of these gray-zone activities and the potential for a crisis to erupt in the area.

Chinese Motivations

Through so-called gray-zone activities, which operate in the space between peacetime and wartime, the PLA is pursuing a campaign of military coercion and attrition designed to reduce Taiwan’s air strength, and to increase pressure on the garrison stationed on Pratas Island. This gray-zone conflict is deliberate, calculated, and has gained significant traction in recent years. While it is characterized by measured aggression and carefully choreographed shows of force, it is not a war of air engagements. It is defined by coercive, aggressive action, but it is deliberately intended to avoid crossing the threshold of an actual military attack on either Taiwan or Pratas Island.

China’s continuous “combat readiness cruises” targeting Taiwan’s southwest airspace serve several purposes. First, they indicate that in a “Taiwan military scenario,” this would be the airspace that China intends to control from the very beginning. Second, they show that China plans to cut off Pratas Island from external communications. Given the island’s position—far from Taiwan, and beyond the median line of the Taiwan Strait—this could signal that China believes that the United States and Japan may not take any concrete military response to such an action. Third, they demonstrate that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) believes that it could deter or delay the US military from entering the Bashi Channel or the South China Sea during a Taiwan crisis by pursuing an anti-access and area denial (A2AD) strategy. Fourth, they show that China could use its punishment tactics to prevent the United States from “using Taiwan to contain China” (以台制中) and the Tsai Administration from “relying on the United States to seek independence” (倚美謀獨), both common accusations in PRC propaganda. Fifth, they demonstrate the PLAAF’s ability to wear down Taiwan fighter jet pilots through an air campaign of attrition, while also upgrading its cross-theater coordination between the Eastern Theater Command (東部戰區) and the Southern Theater Command (南部戰區).

Chinese fighter jets have gradually increased the number of intrusions into Taiwan’s southwestern ADIZ from 380 sorties in 2020 to 961 sorties in 2021. Taking the whole year of 2021 as an example, the PLAAF intruded into the airspace southwest of Taiwan with a variety of planes, including slow-speed aircraft (Y-8, Y-9, Y-20 and Air Police 500)—used in a total of 361 sorties—and high-speed aircraft (J7, J-10, J-11, J-16, Su-30)—used in a total of 533 sorties. These were accompanied by H-6K bombers (60 sorties) and helicopters (seven sorties). Most of the bombers were flying in the outermost periphery of the southwest corner of Taiwan’s ADIZ, close to the northeast shore of Pratas Island.

Notably, the penetrated area is not part of Taiwan’s territorial airspace, and the PLA’s intrusions are unlikely to cause a strong reaction from Taiwan or the United States. However, the intrusions demonstrate that the PLA would be able to interdict Taiwan’s air resupply missions to Pratas Island, and leave resupplies via sea as the only alternative. Taiwan faces many difficult questions in dealing with gray-zone activities involving Pratas Island: for example, when and how might China cross the threshold and take actual steps to seize the island? Can the PRC achieve domination of the island without firing a shot? Will the PRC launch a blockade of the island, potentially leading to a capitulation of Taiwan’s beleaguered defensive forces on the island? Under all these circumstances, if the Tsai Administration were forced to respond with its military forces, it would likely follow the principle of proportionality—instead of expanding the military confrontation—in order to avoid any unmanageable or irreversible consequences for cross-Strait relations. This situation has been exacerbated by the crisis in August 2022, which indicated that Taiwan’s leaders could quickly shift their focus away from the remote island in the South China Sea.

Security Implications

Pratas Island is 260 kilometers (140 nautical miles) away from Shantou, in China’s Guangdong Province, 315 kilometers (170 nautical miles) southeast of Hong Kong, 740 kilometers (400 nautical miles) northwest of Manila, and 450 kilometers (240 nautical miles) away from Kaohsiung, Taiwan. While the island is of significant geostrategic importance along the major sea route connecting the Pacific and Indian oceans, it is not considered to be explicitly covered by the Taiwan Relations Act, which only mentions the islands of Taiwan and the Pescadores (Penghu Islands, 澎湖群島). Pratas Island was first placed under the administration of Kaohsiung in 1939 and is now treated as a component part of the city. [1] Due to the island’s unique position, it seems likely that US reactions to a contingency in Pratas Island would be different from a military crisis involving Taiwan or Penghu. Regarding the security situation of Pratas Island, Japanese scholars Yoshiyuki Ogasawara and Rira Momma have given stern warnings of the possibility of a Chinese military attack. The US think tank Center for a New American Security (CNAS) has also described the dilemma that could face Taiwan and the United States should hundreds of hostages from Pratas be taken to mainland China. This could prevent both Taiwan and the United States from being able to take concrete actions to restore the status quo, forcing them to accept China’s annexation of a piece of its long-claimed territory.

In the recent past, when US aircraft carriers assembled in the Philippine Sea to the east of Taiwan for drills, Chinese fighter planes have often penetrated Taiwan’s ADIZ and flown close to the southeast corner of Taiwan. From October 1 to 4, 2021, the carriers USS Ronald Reagan (CVN76), USS Carl Vinson (CVN 70), and HMS Queen Elizabeth (R 08), as well as the Japanese helicopter destroyer JS Ise (DDH 182), conducted unprecedented sea drills in the eastern waters of Taiwan and the Philippine Sea. In response, Chinese fighter jets extended their “combat readiness cruise” routes into Taiwan’s southeast ADIZ. China dispatched a total of 145 fighter aircraft on October 1 (38), 2 (39), 3 (16), and 4 (52), significantly exceeding normal levels. China’s intrusions into Taiwan’s ADIZ have not only targeted Taiwan and Pratas Island, but also US military activities near Taiwan. In retaliation to US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s trip to Taiwan on August 4, 2022, the PLA launched five missiles from Zhejiang and Fujian into eastern waters of Taiwan and Japan’s claimed exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

In the conflict between the United States and China involving Taiwan, it is necessary to ensure freedom of navigation in the South China Sea waterway. If the United States controls the waters near Pratas Island in the northeastern part of the South China Sea, it will become more difficult for China to pass through the Bashi Channel. If China controls the same waters, it could further counter US military intervention in both the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea. The PRC has already changed the status quo of a median line in the Taiwan Strait and denied the legality of the Taiwan Strait as international waters.

President Joseph Biden has emphasized the need for an international coalition of like-minded democratic countries to maintain security, and to encourage the internationalization of the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait free from China’s domination. This indicates that the waters surrounding Taiwan can no longer be as peaceful as they were during the Cold War era. Secretaries of State Mike Pompeo and Antony Blinken successively reaffirmed that the US-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty will apply to Philippine naval ships and troops under attack. In doing so, they linked military outposts occupied by the Philippines in the South China Sea with the United States security commitment.

However, Taiwan and the United States have no formal diplomatic relations, and it is not clear whether Pratas Island will be covered by the TRA. If China were to attack or blockade Pratas Island, which is larger than any reefs occupied by the Philippines in the Spratly Islands, will the United States sit tight and only issue verbal condemnations? Pratas Island dwarfs an almost submerged reef named the Scarborough Shoal, disputed among Taiwan, China and the Philippines. If the Obama Administration once took military actions to forestall Xi Jinping (習近平) from constructing the Scarborough Shoal into an artificial island in 2016, then the Biden Administration needs to watch China’s military postures around Pratas Island more closely.

Why Itu Aba is Safer than Pratas

When comparing the security situation of Pratas Island with that of Taiwan’s Taiping Island (Itu Aba, 太平島), major differences are clear. Taiping is surrounded by reefs occupied by Vietnam (Sand Cay, Dunqian Shazhou, 敦謙沙洲) and China (Gaven Reef, Nanxun Jiao, 南薰礁), both located within 12 nautical miles. When attacking Taiping Island to punish the Tsai Administration, Beijing cannot ignore—from a political point of view—the risks posed to Sand Cay, located to the east of Taiping. From a military perspective, Hanoi will not invade Taiping simply because it would meet strong countermeasures from Taiwan and the PRC. By comparison, Pratas Island lacks the geographic protections enjoyed by Taiping. Chinese fighter jets would most likely use gray zone operations to target Pratas, including flying H-6K bombers over the island before landing on Yongxing Island (永興島) or the Xisha Islands (Paracel, 西沙群島), harassing Taiwan Coast Guard patrol ships in law enforcement operations inside Taiwan’s contiguous zone, interfering with air supplies to Pratas from Taiwan, and conducting military exercises in important waterways.

Beijing knows all too well that Pratas Island cannot realistically be controlled by any of the ASEAN claimants involved in regional territorial sovereignty disputes. China claims the final text of the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea, negotiated through ASEAN, is intended to be completed as early as possible. The PRC has deliberately attempted to exclude the Paracel Islands and Pratas Island from the code, arguing that it only applies to the Spratly Islands. While taking actions to delay finalization of the Code of Conduct, and utilizing time for greater control over the South China Sea, COVID-19 affects the consultation process. Furthermore, other political factors are also at play: If the PRC takes any military actions against Taiping or occupies other new reefs in the Spratly Islands, Xi Jinping’s dream of building a “community of common destiny” will suffer a grave setback.

China’s gray-zone strategy has changed the status quo of security in the vicinity of Taiwan. For example, the median line of the Taiwan Strait is now crossed on a regular basis, and the southwest corner of Taiwan’s ADIZ faces frequent intrusions. China’s overreaction to Pelosi’s trip—bracketing Taiwan with missiles, rockets, destroyers and fighter jets—has led international media to focus on the increased tensions in the Indo-Pacific region. This also gives major countries the impression that the Taiwan Strait has a high possibility of military conflict. While this is important, such a focus on the Taiwan Strait risks ignoring China’s gray-zone tactics against Pratas Island. In July 2020, former US Secretary of Defense Mark Esper warned that “the PLA’s large-scale exercise to simulate the seizure of the Taiwan-controlled Pratas Island is a destabilizing activity that significantly increases the risk of miscalculation.”

Conclusion

China recognizes that the Biden Administration has used mechanisms such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), the Australia-UK-US (AUKUS) security alignment, the US-Japan alliance, and the US-Philippines-Vietnam tripartite coordination to strategically contain China in the South China Sea. Pratas Island has been increasingly under Chinese threats, posing a growing risk to both Taiwan and the sea lines of communication in the South China Sea. If the PRC can control Pratas Island, then it could turn the island into an important strategic base asset, forcing the United States to contend with serious security consequences in the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait. Taiwan is not China’s only target. In the case of a blockade of Pratas Island, China will be able to reduce the ability of the United States military to freely enter and leave the Bashi Channel and the South China Sea. Policymakers and defense planners in the United States, Taiwan, and like-minded allies and partners should not underestimate the security implications and potential for crisis surrounding Pratas Island.

The main point: While recent events have resulted in increased international attention to tensions in the Taiwan Strait, China’s gray-zone tactics targeting Taiwan’s Pratas Island have been largely ignored. Given Pratas’ strategic importance, this could be a dangerous oversight.