Taiwan’s energy security is at a critical inflection point. According to the Taiwan Bureau of Energy’s (BOE, 經濟部能源局) 2022 Energy Statistics Handbook, the country relies on imported energy sources for 96.86 percent of its energy needs. In recognition of this strategic dependency, the country has made great strides in growing the capacity of its renewable energy sector. In the long term, this coal-replacement strategy will improve both energy supply access and sustainability. In turn, this will directly reduce Taiwan’s reliance on imported energy and enhance its energy security.

Despite these improvements in diversifying the sources of electricity generation, Taiwan still faces extreme challenges in the oil industry. Petroleum products are the primary source of energy for Taiwan’s transport sector, a major energy source for the industrial sector, and a crucial input for many other non-energy processes. Both Taiwan’s civilian and military segments require these petroleum products to function—whether driving, flying, or sailing. [1] However, Taiwan is 99.75 percent reliant on imported petroleum and does not have strike-resistant storage facilities or a single Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) base. Instead, the responsibility for managing Taiwan’s petroleum reserves is delegated to the civilian-led oil industry. This stands in stark contrast to the SPR systems employed by Japan, South Korea, and the United States, which are managed by government agencies. Given rising geopolitical tensions and recurring Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) blockade drills, Taiwan must take immediate action to strengthen and secure its oil sector.

How can Taiwan best protect its oil industry? How can Taiwan build resiliency and ensure strategic oil reserves for both military and civilian use? This two-part article series will seek to answer these questions by critically analyzing Taiwan’s oil supply chain, identifying its key vulnerabilities, and offering policy recommendations. Drawing on supply chain modeling from the American Petroleum Institute, this analysis examines Taiwan’s oil industry through six linked elements: 1) production; 2) transportation (shipping/pipelines); 3) short-term storage; 4) refining capacity; 5) terminal capacity; and 6) point of use. This first article (of a two-part series) examines Taiwan’s crude oil supply chain during the first three phases of production, transportation, and short-term storage.

Oil Supply Chain Overview

Taiwan’s Petroleum Administration Act (石油管理法) and Measure Governing Oil in Emergency Management (緊急時期石油處置辦法) are the primary regulations governing Taiwan’s oil industry and strategic reserves. [2] In general, the island’s oil industry is led by two companies: the publicly held CPC Corporation Taiwan (台灣中油股份有限公司) and the privately held Formosa Petrochemical Corporation of Formosa Plastics Group (FPCC, 台塑石化股份有限公司). The CPC dominates the Taiwan economy, with an overall market share of 77.5 percent (79.6 percent of gasoline consumption, 77.2 percent of diesel, 96.4 percent of fuel oil, and 60.3 percent of aviation fuel). In combination, these two players operate three refineries and directly manage all stages of oil supply chain operations in Taiwan. This includes the management, oversight, and inspection of Taiwan’s strategic reserves. The government of Taiwan does not independently operate any SPR bases or facilities; instead, it chooses to contract these reserves through the Petroleum Fund, paying more than NTD $2 billion (USD $62.8 million) annually to the CPC and FPCC. [3] Of note, Article 56 of Taiwan’s Petroleum Administration Act (石油管理法) does not cover military stockpiles. Accordingly, there is no official information published about military reserves, and even non-official reporting about these stockpiles is limited.

Phase One: Production

During the production phase, crude oil is extracted from the ground or from the ocean. This process requires the identification and exploration of oil fields. Next, extraction facilities must be designed and constructed according to the oil fields’ specific requirements. This process is time-consuming, expensive, and often litigious.

Taiwan’s oil industry is one of the oldest in the world. Following the invention of modern oil wells in the late 1840s and 1850s, Miaoli County began petroleum extraction in 1877. Taiwan built its first deep well in 1959 in Jinshui and underwent a period of exploration and rapid development, reaching peak crude oil extraction in 1978. Despite these early successes, the Bureau of Energy reports that the country is now 99.75 percent dependent on foreign crude oil imports. In fact, for the past twenty years, Taiwan’s dependency on foreign imports of crude oil has hovered between 99.91 and 99.75 percent, while less than 0.25 percent of Taiwan’s crude oil is produced domestically. In 2023, CPC’s overseas production efforts yielded 5.68 million barrels of crude oil, a paltry sum compared to Taiwan’s total import level of 384.8 million barrels.

Efforts to expand Taiwan’s domestic crude oil production would reduce its import dependency. However, given Taiwan’s geography and the lengthy and costly nature of modern oil field exploration, this should not be the Taiwanese government’s primary area of focus.

Phase Two: Transportation

After the production phase, crude oil is transported from the extraction site to a short-term storage facility. The crude oil can be transported by rail, roadway, long-haul pipeline, gathering pipeline, or ship. At this stage, the crude oil accumulates for future movement to an oil refinery or other processing facilities. Crude oil could also be re-routed to a Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) location.

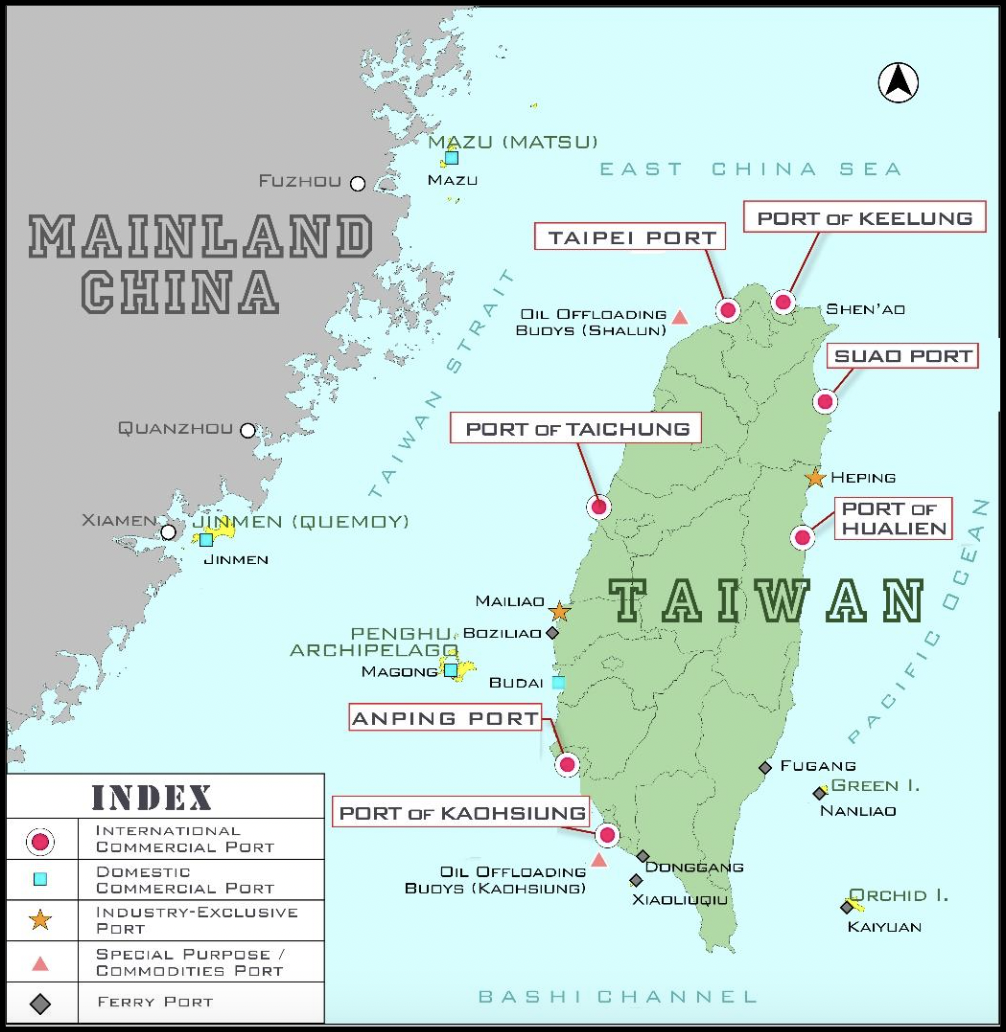

Due to its geography and lack of domestic crude oil production, 99.75 percent of Taiwan’s crude oil is imported by oil tanker via the Taiwan Strait. The majority of crude oil imports are designated for three ports: Kaohsiung, Keelung, and Mailiao.

Graphic: A map of major cities and ports involved in Taiwan’s oil supply chain. (Graphic Source: Taiwan International Ports Corporation)

- The Port of Keelung (基隆港) in the north has two specialized oil terminals, Shen-ao and Sha Lung, located in the western half of the port. This port is near one of CPC’s northern oil refineries.

- The Port of Mailiao (麥寮港), in the county of Yunlin, also has specialized oil receiving facilities in its northern section. This port is industry-controlled and near FPCC’s oil refinery.

- The Port of Kaohsiung (高雄港) in the south has specifically designated twenty-five berths for oil and petroleum products. This port is near one of CPC’s southern oil refineries.

- Additionally, the Port of Suao (蘇澳港) on the east coast has one petroleum product berth.

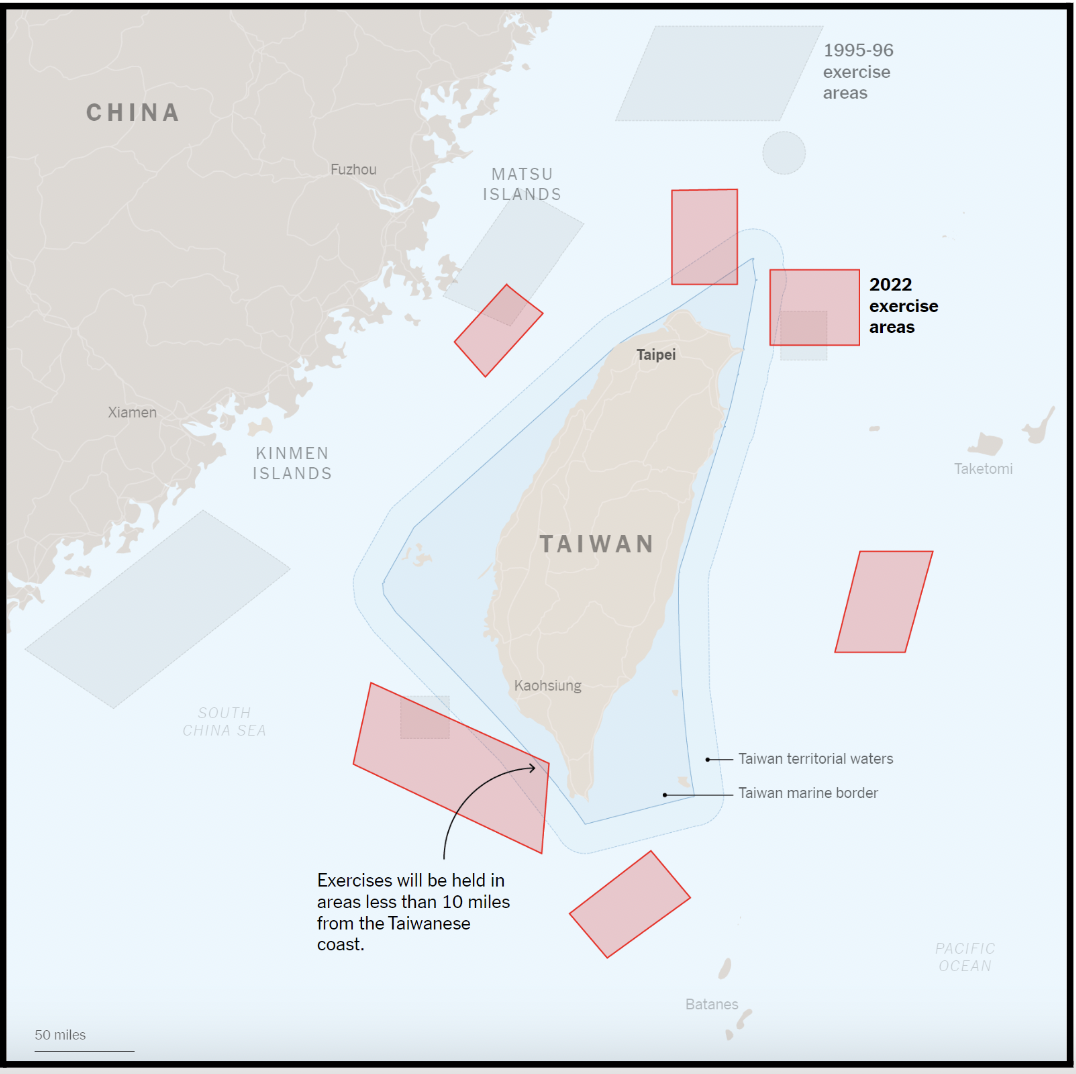

Sustainable seaborne transportation is critical to Taiwan’s crude oil supply and energy security. The country’s primary crude oil receiving ports are all located on the west coast of Taiwan. While this is the most economically feasible and profitable location for oil imports given existing shipping lanes, it is also the most vulnerable to Chinese PLAN operations. Examining a recent report from The New York Times, it is apparent that Chinese blockade efforts are focused on the main oil importing ports, Keelung and Kaohsiung—with these ports being explicitly targeted during PLAN drills.

Graphic: A map of Chinese military drills conducted in August 2022. Two of the areas of activity were in close proximity to Keelung and Kaohsiung. (Graphic Source: New York Times)

The government must consider the development of oil industry infrastructure on Taiwan’s east coast. The eastern coastline, while ravaged by extreme weather events and rougher waters, is further outside the zone of PLAN operations. This development proposal calls for increasing the number of ports, berths, and facilities specialized for transporting petroleum. While these locations may incur upfront operating losses, they will be critical for ensuring short- and medium-term access to crude oil imports.

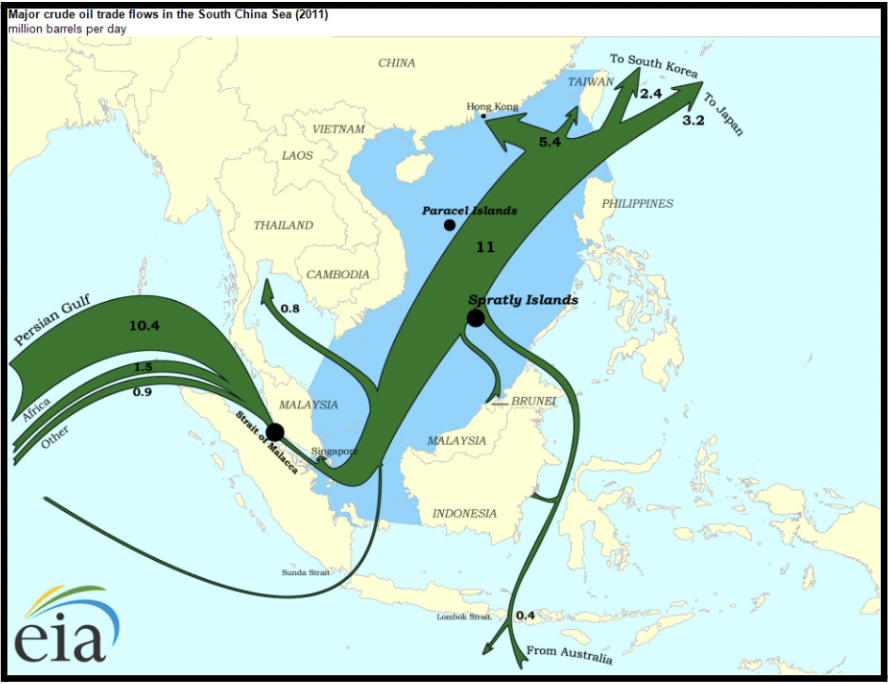

At first glance, this proposal may seem extreme. However, in comparison, all of Japan’s oil infrastructure is located on its eastern-exposed or central side. Although Japan’s archipelagic geography is different, its five petroleum ports (Chiba, Yokohama, Yokkaichi, Mizushima, and Osaka) are all oriented to the east or south. As a result of this orientation, crude oil shipping from the Middle East already transits around the east coast of Taiwan to reach Japan’s ports. While this proposal does not directly counter a PLAN blockade, it does significantly increase the potential for sustainable access to oil imports. Given that Taiwan is wholly reliant on crude energy imports, this ensured access for oil tankers is critical to Taiwan’s energy security.

Graphic: A 2011 map showing crude oil trade flows in the Indo-Pacific. (Graphic Source: US Energy Information Administration)

Phase Three: Short-Term Storage

Short-term storage facilities hold crude oil at production sites, transportation hubs, ports of call, and refineries. These facilities are critical to managing the supply of crude oil.

Taiwan has short-term storage facilities at its primary oil-related ports of call: Keelung, Mailiao, and Kaohsiung. From the port, crude oil is transported to Taiwan’s Taoyuan Refinery, Mailiao Refinery, or Dalin Refinery. A relatively small portion of crude oil is also transferred to CPC or FPCC strategic petroleum reserve long-term holding tanks. However, there is not publicly available information about the SPR transfers. Drawing on information from CPC and FPCC, each refinery maintains its own short-term storage facilities:

- The Taoyuan Refinery (桃園煉油廠) sources its crude oil from the Shalun fuel depot. The Shalun Fuel Depot has 15 large tanks at full operational capacity and can hold 10.69 million barrels of crude oil.

- The Mailiao Refinery (麥寮煉油廠) has 28 above-ground tanks. At full operational capacity, the refinery can hold 22.89 million barrels of crude oil.

- The Dalin Refinery (大林煉油廠) has developed offshore mooring pontoons, wharves, and facilities to facilitate short-term transfer and storage of crude oil.

Based on the Petroleum Administration Act, aggregate storage facilities are only required to store 60 days of crude oil (roughly 64 million barrels across all storage facilities for both companies). Given the potential for a long-term economic blockade focused on the east coast, this supply may be insufficient. Additionally, these refineries and their coastal tanks are proximate to the Taiwan Strait and thus are vulnerable to PLA and PLAN artillery and missile attacks. Finally, these commercial, short-term storage tanks are not designed for impact protection.

The government of Taiwan should consider: 1) developing national underground SPR bases within the Central Mountain Range; and 2) hardening existing short-term storage structures. Existing Chinese missile technology, such as the DF-15C ballistic missile, has both the range and the capability to penetrate over 25m of concrete, but cannot penetrate dense mountain terrain. For comparison, the island nation of Japan manages 10 national oil storage bases, while South Korea manages eight national oil storage bases. Although both options are expensive, Taiwan requires secured large-scale facilities to hold crude oil.

In comparison, Japan’s government owns nearly 30 percent of the storage capacity (including both short-term and long-term) in the country. These national oil storage facilities for crude oil and other refined petroleum products are spread across a variety of holding facilities, including underground rock caverns, in-ground tanks, and above-ground tanks. Similarly, South Korea’s government, in combination with international joint oil stockpilers, holds approximately 35 percent of the oil supply in national storage facilities geographically spread throughout the country. The United States’ SPR crude oil storage capacity is based primarily underground in salt caverns. Taiwan must consider how to protect its crude oil reserves in the event of an emergency or military conflict.

Taiwan must address these critical energy security shortcomings to ensure sustainable access to petroleum for its transportation and industrial sectors. A failure to ensure oil access may lead to second-order failures for both civilian and military use. It is critical that Taiwan seriously considers enhancing the resiliency of its crude oil supply chain.

The second article of this series, forthcoming in October 2023, will examine Taiwan’s latter three phases of oil processing (i.e., refinement, terminal storage, and final point of use).

The main point: Taiwan must take action to build resiliency and strengthen its oil supply chain. Taiwan should address critical weaknesses in crude oil transportation and short-term storage in order to ensure sustainable access to petroleum in times of crisis.

[1] There are not yet viable alternatives to petroleum-based fuels for Taiwan’s military equipment. This includes all types of aerial vehicles, ground vehicles, seaborne vessels, and maintenance and operations supplies.

[2] In the case of Taiwan, oil is defined as petroleum crude oil, bituminous crude oil, and petroleum.

[3] Please see the Taiwan’s Petroleum Administration Act (石油管理法) for additional information on financing and the sources of the Petroleum Fund.