Introduction

The Regional Cooperation Economic Partnership (RCEP) is a major trade agreement featuring nations across the Indo-Pacific, with outsized representation from Southeast Asia. [1] However, the RCEP has never included Taiwan. Considering Taiwan’s strong efforts to shift trade from China to Southeast Asia under the 2016 New Southbound Policy (NSP), RCEP members have few obvious economic reasons to exclude Taiwan. Rather, it is the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) economic and political influence that significantly contributes to Taiwan’s exclusion, similar to how the PRC wields its influence to limit Taiwan’s access to other international organizations like the United Nations. Given China’s considerable market power, most RCEP member countries tend to follow China’s stance. [2] However, Taiwan’s economic heft as the world’s eighth-largest economy suggests that RCEP members may be incurring some kind of ongoing costs by excluding Taiwan from the trade liberalizing framework. [3]

This article uses economic modeling to determine whether RCEP members are facing ongoing costs by excluding Taiwan from the existing trade bloc. It will do this by estimating the net change to RCEP members’ consumer welfare and gross domestic product (GDP) were Taiwan suddenly allowed to join RCEP. The study will also predict the economic impacts on Taiwan’s simulated RCEP membership on four other targets: Taiwan, China, the United States, and the rest of the world. While the United States is not a member of RCEP, the ripple effects of reduced trade barriers between Taiwan and RCEP economies will have an impact on the United States’ trade in the Indo-Pacific. [4] Given that the United States is a key geopolitical supporter of Taiwan, the question of whether Taiwan’s theoretical RCEP membership would impact the US economy is relevant. While Washington may have geopolitical reasons for supporting or opposing Taiwan’s RCEP membership, there is little understanding regarding whether the United States would face economic costs should Taiwan join.

Methodology

We employed the Computational General Equilibrium (CGE) model under the Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) as the primary methodology for conducting this policy experiment and measuring the shock. Known for its robust capabilities and detailed modeling of a country’s global trade activities, GTAP is a key tool for analyzing trade shocks and conducting counterfactual simulations of regional integration. [5]

To simulate Taiwan’s potential inclusion in the RCEP as part of Taiwan’s New Southbound Policy, three key components are necessary: data, models, and experiments. For our policy experiment, we first utilized the GTAP 10 database, which is based on input-output tables of international trade published by governments worldwide. [6] Second, we adopted the standard GTAPv7 General Equilibrium model setup, widely used to represent open economies, using the default settings for the model. [7] Lastly, we introduced a shock (an immediate reduction) to the import tariffs between Taiwan and RCEP countries as a way to simulate Taiwan’s sudden membership in the organization.

In order to measure the costs or benefits to RCEP countries, Taiwan, the United States, and the rest of the world that might stem from Taiwan’s sudden RCEP membership, we employed the equivalent variation (EV) measure, which measures how changes in prices affect consumer welfare. Positive EV means that consumers are able to purchase more at the same level of income. We also modeled the impact to the GDP of RCEP nations, Taiwan, the United States, and all other countries combined, should Taiwan join—which is referred to as VGDP.

We first modeled the economic impacts of a sudden 10 percent reduction in bilateral tariffs between RCEP nations and Taiwan, before modelling more significant tariff reductions, increasing in increments to 100 percent. We also applied a 10 percent multiplier to these tariff shocks to simulate the knock-on effects of consumer spending.

Simulation Results

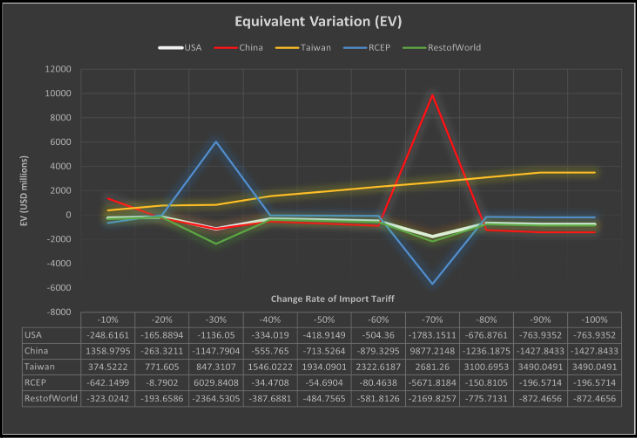

Figure 1 shows the welfare change measured by the monetary EV, for tariff reductions ranging from 10 percent to 100 percent. The vertical axis indicates the EV value, and the colored lines represent five groups of countries that are the focus of this study: the United States, China, RCEP nations, Taiwan, and a combined group for the rest of the world, which we use to derive our results.

Figure 1: A graph showing the equivalent variation (EV) in consumer welfare for five country groupings should Taiwan experience sudden tariff reductions with RCEP members (Source: Created by the author.)

Figure 1: A graph showing the equivalent variation (EV) in consumer welfare for five country groupings should Taiwan experience sudden tariff reductions with RCEP members (Source: Created by the author.)

As can be observed from Figure 1, only Taiwan experiences consistent positive EV in models simulating sudden tariff reductions between Taiwan and RCEP member nations. The EV—which represents changes in consumer welfare—trends more positively as tariffs reductions precipitated by RCEP membership grow larger.

However, the EV is inconsistent or negligible for other country groupings should Taiwan join RCEP. China and RCEP nations experience either very little EV or sudden spikes and surges—which may be explained by model eccentricities.

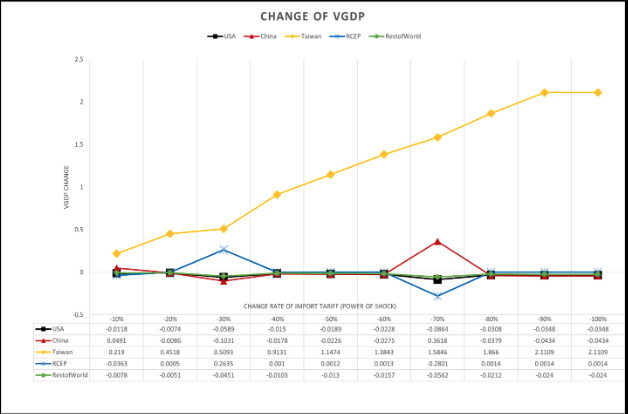

Figure 2: Graph simulating the changes in GDP precipitated by tariff reductions between Taiwan and RCEP members, ranging from 10 to 100 percent. (Source: Created by the author.)

Figure 2 shows the change in VGDP for the five country groupings triggered by a set of sudden tariff reductions between Taiwan and RCEP nations. As can be seen from Figure 2, Taiwan—represented as the yellow line—is again the only economy to experience consistent benefit following various tariff reductions. The potential increases to Taiwan’s GDP range from around 0.25 percent at a 10 percent tariff reduction in trade with RCEP nations, to over 2 percent at a 100 percent tariff reduction. Other country groupings, such as China, the United States, and RCEP nations, experience little to no consistent GDP change. The weak effect of Taiwan’s simulated RCEP membership on other RCEP members and China is surprising, especially given that Taiwan’s volume of trade between these partners is sizable.

Policy Implications

Several key conclusions can be drawn from the graphs. Firstly, the results suggest that Taiwan would clearly benefit if invited to join the RCEP. As shown in the results table, joining RCEP could provide benefits to Taiwan ranging from USD 354 million to USD 3,490 million. Even if Taiwan cannot enter the RCEP for geopolitical reasons, Taipei should consider accepting invitations for economic cooperation with Southeast Asian countries, particularly regarding tariff reductions.

Secondly, China appears to have few economic incentives to alter the current situation of Taiwan’s exclusion from the RCEP, since including Taiwan in RCEP does not result in significant economic growth for China and the impact on China is relatively small. This reconfirms the presumption we had made: that Beijing is highly likely to direct the current exclusion of Taiwan. The asymmetry in economic impacts between Taiwan and China makes Taiwan’s participation in the RCEP a politically powerful tool for China to use in dealing with Taiwan. However, as you can see in the diagram provided, in this general model, the impact on China is not linear. If Taiwan and the member states’ tariffs are reduced to around 70 percent from the benchmark model, China could also benefit substantially. This indicates that China’s usage of political influence against Taiwan incurs some economic loss for China as well.

Thirdly, the models suggest that RCEP countries themselves stand to benefit very little from Taiwan’s membership when the tariff decreases are small. However, if the overall tariff decreases are larger than 30 percent from the benchmark model, RCEP countries could see an increase in their GDP growth. The Taiwanese government should not overlook these benefits. As Taipei continues to promote their existing New Southbound Policy—which aims to engage Southeast Asian nations (all of which are RCEP members)—the Taiwanese government should highlight the benefits that Southeast Asian partners would gain if the tariff rate is lowered past 30 percent. Additionally, suppose the membership of the RCEP is unattainable for Taiwan for a period of time. In that case, the Taiwanese government should still seek any bilateral trade agreements that could lead to a significant reduction in tariffs of goods between RCEP member countries and Taiwan.

Finally, the United States is expected to experience only minor negative economic impacts if Taiwan joins the RCEP (assuming that the United States is still not the member state of the RCEP). Because the negative effects are minor and a stronger Taiwan economy benefits the United States’ geopolitical interests, the United States gains more from Taiwan’s inclusion in the RCEP than from its exclusion—especially considering Taiwan’s unique geographical location and its role in the global supply chain of semiconductor products. Therefore, we advise the US government to address China’s coercion of Taiwan through any available channels, and in the best scenario, both the United States and Taiwan should seek to join the RCEP to both maximize the benefits and reduce negative impacts.

Still, the issue of Taiwan’s exclusion from the RCEP represents a small part of a larger problem. Although we can estimate the potential economic costs of Taiwan’s exclusion from the RCEP using modeling, the costs of preventing Taiwan’s exclusion from other international organizations are more difficult to determine, yet far greater. Taiwan’s exclusion from the United Nations, the World Health Organization, and International Monetary Fund blocked Taiwan from sharing its successful responses to global challenges—such as COVID-19, the 1998 Asian Financial Crisis, and the 2008 Subprime Mortgage Crisis—with other countries. By allowing China’s influence to block Taiwan’s participation in trade agreements and international organizations, economies and populations around the world will suffer the effects.

Conclusion

Taiwan’s unique role in the Asia-Pacific has recently evolved into a delicate balance between economic benefits and political tensions stemming from the world’s two most powerful countries, China and the United States. Taiwan has already signed a bilateral agreement with China, known as the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA, 海峽兩岸經濟合作架構協議). Currently, Taiwan and the United States are continuing to discuss the terms in the Economic Prosperity Partnership Dialogue (EPPD, 台美經濟繁榮貿易倡議), which is part of the framework announced by the Trump Administration in April 2025.

By modeling the effects of reduced tariffs, this article explored the economic benefits and losses that occur from Taiwan’s exclusion from the RCEP. Through this modeling, it was revealed that Taiwan is the main beneficiary economically, although there are also economic benefits for RCEP nations and China. Additionally, while the United States would experience some negative effects, the impacts are relatively minor. From these results, the Taiwanese government may consider reevaluating the goals and strategies of Taiwan’s New Southbound Policy while preparing potential proposals to join the RCEP. The current NSP appears to focus more on recruiting Southeast Asian students, tourists, and migrant workers to Taiwan, as well as encouraging Taiwanese firms to invest in Southeast Asia. As a result, it is more oriented towards increasing trade in the service sector. However, Taiwan could also benefit from lower tariffs with RCEP countries—many of which are also NSP partner nations. Therefore, if formal membership in the RCEP is not guaranteed in the near future, the Taiwan government should consider negotiating trade agreements with the RCEP nations individually.

The main point: Taiwan would benefit significantly from membership in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Its exclusion seems politically driven, resulting in real economic costs for RCEP, China, and global welfare. Taiwan should reevaluate its New Southbound Policy, pursue bilateral tariff reductions, and prepare proposals for future RCEP negotiations. This situation also highlights the broader impact of Taiwan’s exclusion from other international organizations.

[1] Nancy Bernkopf Tucker, Dangerous Strait: The U.S.–Taiwan–China Crisis, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), https://doi.org/10.7312/tuck13564.

[2] Pasha L. Hsieh, “The RCEP: New Asian Regionalism and the Global South,” Institute for International Law and Justice (IILJ) Working Paper, 2017, 4.

[3] Richard E. Baldwin, “Multilateralising Regionalism: Spaghetti Bowls as Building Blocs on the Path to Global Free Trade” in Global Trade, (London: Routledge, 2017), 469–536; Kerry A. Chase, Trading Blocs: States, Firms, and Regions in the World Economy, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2009); Paul Krugman et al, “The Move toward Free Trade Zones,” Economic Review 76, 6 (1991): 5.

[4] Hiro Lee and Michael G. Plummer, “Assessing the Impact of the ASEAN Economic Community,” OSIPP Discussion Paper 11E002, Osaka School of International Public Policy, Osaka University, 2011 https://ideas.repec.org/p/osp/wpaper/11e002.html.

[5] Erwin Corong et al., “The Standard GTAP Model, Version 7,” Journal of Global Economic Analysis 2, 1 (2017): 1–119. https://doi.org/10.21642/JGEA.020101AF.

[6] Thomas Hertel, “Global Applied General Equilibrium Analysis Using the Global Trade Analysis Project Framework,” in Handbook of Computable General Equilibrium Modeling SET, Vols. 1A and 1B, ed. Peter B. Dixon and Dale W. Jorgenson, (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2013), 815–876, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-59568-3.00012-2.

[7] Thomas Hertel et al., Global Trade Analysis: Modeling and Applications, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997) Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP), Department of Agricultural Economics, Purdue University, https://www.gtap.agecon.purdue.edu/resources/res_display.asp?RecordID=4840.