In February 2022, Switzerland took a decision that grabbed global attention. A few days after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Federal Council—Switzerland’s executive body—announced that it would adhere to the European Union’s sanctions regime on Russia. While some observers have described the move as an historical departure from Switzerland’s traditional foreign policy, it was in fact the latest example of how Bern has adapted its neutrality since the end of the Cold War. Switzerland has, for example, joined previous sanctions regimes and participated in NATO’s Partnership for Peace. Furthermore, Switzerland joined the United Nations in 2002, which further signaled a willingness to combine the concept of neutrality with more active engagement in the international system.

Switzerland’s decision regarding sanctions on Russia was nonetheless remarkable due to the speed at which it came. Moreover, it was extraordinary in that it aligned Switzerland with the EU on a high-stakes security crisis, and had major economic implications. Switzerland’s decision also sets a precedent that could soon face a more complex test—a conflict over Taiwan.

The Asia-Pacific region is a geopolitical hotspot, with the Taiwan Strait context particularly worrying: an increasingly assertive China insists on pursing unification, while most Taiwanese reject this and embrace a distinct identity. With both peaceful unification and independence unachievable in the near term, the status quo is growing increasingly unstable and could potentially unwind into armed conflict. From Beijing’s perspective, time is not on its side. As Taiwanese identity grows stronger, achieving peaceful unification becomes less likely. The Chinese Community Party (CCP, 中國共產黨) fears that further delay could lead to permanent separation.

A Taiwan contingency could unfold quickly—potentially by 2027, as some US officials have warned. While China may aim to be ready for military action by then, readiness does not guarantee intent. Still, rising tensions in the Taiwan Strait demand serious international attention, including from Switzerland. The key question is: In the event of an Asia-Pacific crisis involving Taiwan, would Switzerland respond as it did after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine?

Switzerland’s Growing Stake in the Asia-Pacific

Switzerland was one of the first Western countries to recognize the People’s Republic of China (PRC) (doing so in 1950). Since 2010, Beijing has been Switzerland’s biggest trading partner in Asia and its third-largest globally (after the EU and the United States). The PRC plays a critical role in the Swiss economy because of its profound ties with several major Swiss companies. According to the Embassy of Switzerland in the PRC, China ranks among the top three priority investment markets for numerous Swiss firms. Many key sectors of the Swiss economy—most notably electronics, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals—specifically rely on critical inputs from China. As a consequence, stable and strategic economic relations with Beijing are an essential necessity for Switzerland’s continuous prosperity. Recently, in September 2024, Bern and Beijing began negotiations to upgrade their Free Trade Agreement, underscoring the intensity of their economic relationship.

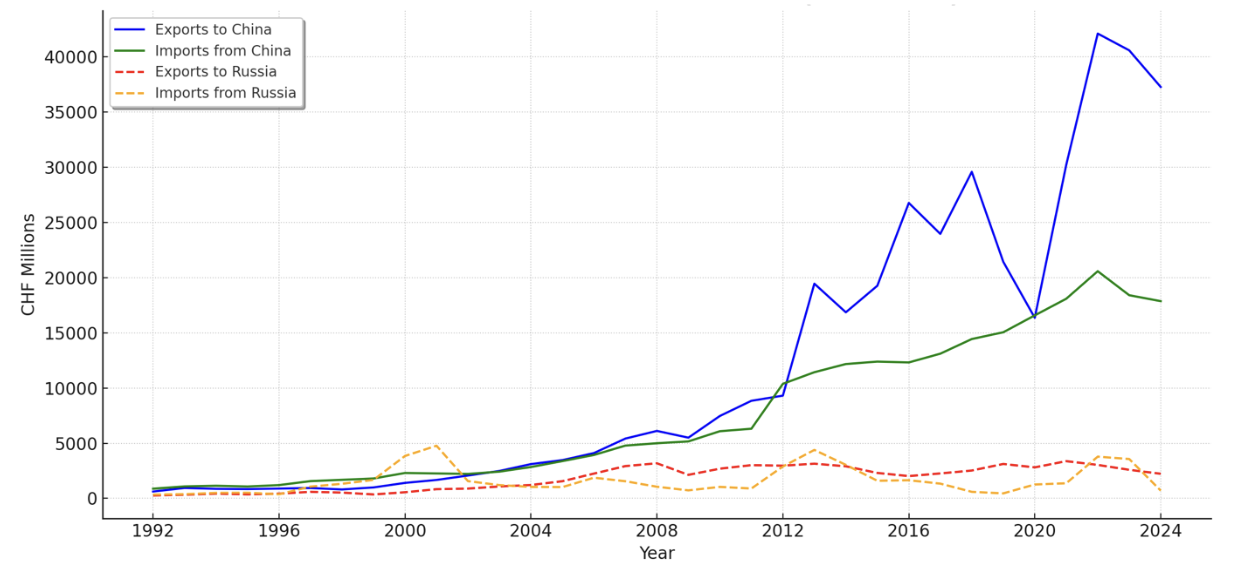

Switzerland’s economic interaction with the PRC far exceeds the scale of its pre-2022 trade with Russia (see Figure 1, below), making the stakes of a confrontation with China considerably higher. While Swiss companies are heavily invested in the Chinese market, their historic economic engagement with Russia has been comparatively modest.

Figure 1: Swiss Trade with China and Russia (1992-2024)

Image: Switzerland trade with China and Russia in millions of CHF between 1992 and 2024. (Data Source: Federal Statistical Office)

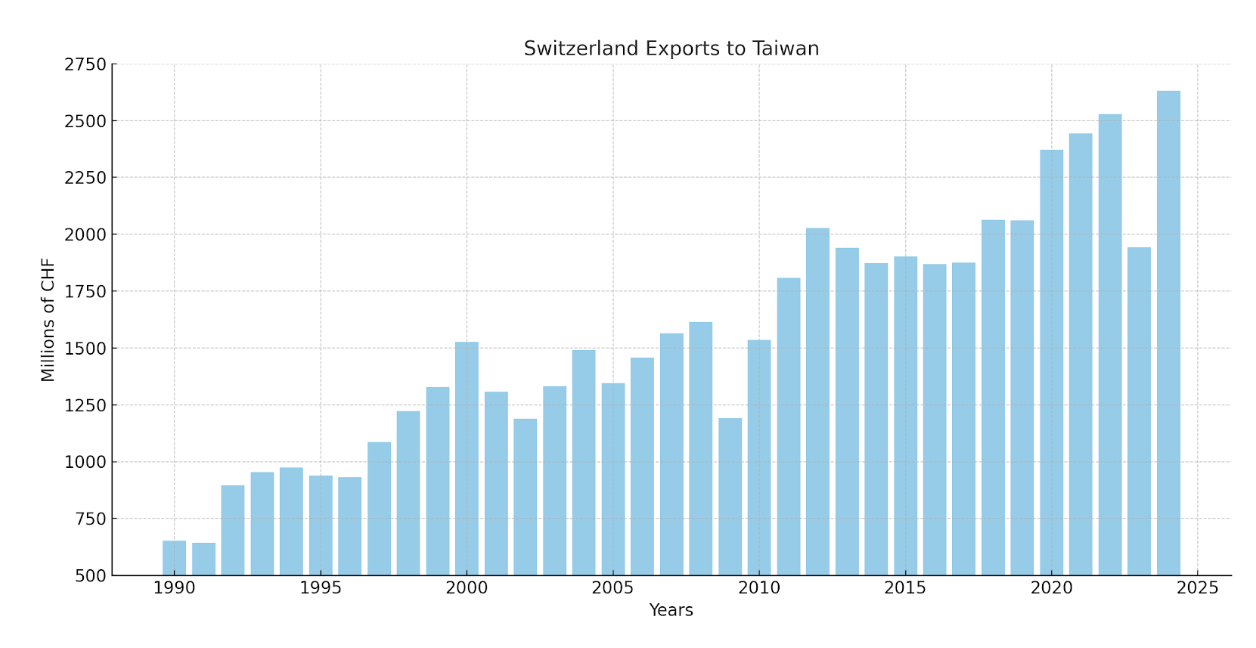

Taiwan was ranked as Switzerland’s fifth-largest export destination in Asia and its 24th-largest worldwide in 2024 (see Figure 2, below). While Taiwan is a significantly smaller market for Switzerland, it plays a critical role in the global semiconductor supply chain. Indeed, Taiwan’s semiconductor industry is an indispensable supplier for an enormous range of advanced civilian and military technology companies: Taipei recorded a market share of 68 percent in the global semiconductor foundry market in 2024. Any disruption to this supply would have serious consequences for Swiss industry, particularly in high-tech manufacturing.

Figure 2: Swiss Exports to Taiwan (1990-2024)

Image: Switzerland exports to Taiwan in millions of CHF between 1990 and 2024. (Data Source: Federal Statistical Office)

This enormous scale of Swiss trade with China, particularly in relation to trade with Taiwan (and indeed Russia), raises critical questions about how far Bern would be willing to go in aligning with Western sanctions in the event of a Taiwan contingency. Unlike in the case of Russia, where the Swiss alignment with EU sanctions concerned a comparatively limited share of its trade, any confrontation involving China would force a far more delicate balancing act between geopolitical values and economic interests. Bern’s economic stakes with Beijing are gigantic in comparison to those with Moscow. In light of this economic context, decoupling from China would be unsustainable for the Swiss Confederation.

This tension is already present in Switzerland’s human rights policy. In order to avoid threatening its relations with Beijing, Bern declined to join the EU’s sanctions against China over its alleged abuses against the Uyghurs. This pragmatic and situational approach risks creating the perception that economic interests are more important than the human rights and democratic values enshrined in the Switzerland’s constitution—a perception that may seriously damage the country’s credibility if Bern takes the same course in a Taiwan crisis.

Although Switzerland views itself as a neutral bridge between competing powers, a conflict in the Taiwan Strait would place it in a delicate position where preserving good relations with both major powers, the United States and China, might prove impossible.

Political and Diplomatic Pressures

Beyond China and Taiwan, the broader Asia-Pacific is a critical trade destination for Switzerland, and profound disruptions in the region would deeply affect the Swiss economy. Countries such as Japan, South Korea, and Australia have emerged as highly important economic and strategic allies. With Japan and South Korea ranking among Switzerland’s top ten trading partners in Asia, and Australia representing a like-minded democracy with shared values on international governance, Bern’s regional assessments cannot revolve around Beijing alone. Deepening its ties across the region not only diversifies Switzerland’s economic portfolio, but also increases its stakes in peace and in the stability of the Asia‑Pacific region.

A conflict over Taiwan would have regional and global repercussions. It could draw in other countries, including Japan due to its proximity along the first island chain, as well as the United States, and to varying degrees partners such as Australia and South Korea. If several of these actors were directly or indirectly involved, Switzerland would face diplomatic pressure to align with their responses that could surpass even what the country experienced during the Ukraine crisis. Washington has sought clarity from its allies on where they would position themselves in the event of a Taiwan contingency. Meanwhile US, Japanese, and Australian forces have intensified joint military exercises in response to Beijing’s growing assertiveness in the region. In this context, Swiss neutrality may become an increasingly unstable policy position.

According to the Bloomberg Economics, the estimated cost of a war in Taiwan would reach around USD 10 trillion—approximately 10 percent of global GDP in 2024—strongly surpassing the economic impact of the war in Ukraine or the COVID-19 pandemic. Any disruptions to shipping routes through the South China Sea and East Asian supply chains would directly affect the Swiss economy.

As mentioned previously, Switzerland maintains deep economic relations not only with China, but also with the United States and the European Union. In the event of a Taiwan contingency, the EU’s response will be particularly decisive. European states increasingly view the challenges taking place in the Indo-Pacific as interconnected with the ones on the continent. Switzerland, situated at the heart of Europe, cannot afford to face political isolation from its neighbors and would almost certainly be pressured by both Brussels and Washington to align with their own stances. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Bern initially hesitated to freeze Russian assets and faced strong criticism from the international community. It ultimately joined EU sanctions—a precedent that would make later non-alignment in the face of military aggression against a democracy like Taiwan difficult to justify.

Could Switzerland position itself as a mediator, drawing on its tradition of good offices? Or would it choose silence to safeguard its economic interests? Whatever the choice, a crisis in the Taiwan Strait would almost certainly become one of the most serious tests of Swiss neutrality in recent history.

The Asia-Pacific: A New Test for Swiss Neutrality and Credibility

In 2020, the Federal Council affirmed that Switzerland’s neutrality is not immutable. Because the Confederation strictly adheres to the “One-China Policy” and therefore does not recognize Taiwan as a state, a conflict in the Taiwan Strait would raise difficult legal questions. Under Switzerland’s law of neutrality, the country is restricted from transferring arms to conflicts between de jure internationally-recognized states. This ambiguity means that Switzerland will need to decide whether, and how, its neutrality law can be applied in a scenario where Taiwan’s statehood is not formally recognized. Alongside this legal dimension, Switzerland’s policy of neutrality is a broader concept whose implementation is determined according to the current international context. This flexibility gives Bern additional room to maneuver, but also carries political risks. Indeed, avoiding sanctions or restrictive actions may be perceived domestically and internationally as the prioritization of economic gain over the defense of international norms.

At the same time, Switzerland identified the global erosion of democracy as of its top foreign policy priorities in its Foreign Policy Strategy 2024–2027. In keeping with this document, the Swiss government has emphasized that promoting democratic values and fundamental freedoms is a strategic national interest. This commitment could face a serious test in the Asia-Pacific region. In fact, Switzerland has recognized the Asia-Pacific’s rising strategic importance and the need to deepen engagement and diversify partnerships in this complex and dynamic region. In today’s context, neutrality cannot simply mean maintaining an equivalent distance between aggressors and victims. A Taiwan contingency would therefore reveal whether Switzerland’s neutrality is truly principled or ultimately pragmatic.

Preparing for a Plausible Crisis

For Switzerland, preparation for a Taiwan contingency involves clarifying how neutrality applies to conflicts involving non‑recognized states and assessing the economic risks of measures against a major trading partner. Acting now would improve the speed and coherence of any future decision.

Switzerland needs a foreign policy that anticipates—not reacts to—future shocks. In this regard, the country’s China Strategy 2021-2024 and Asia G20 Strategy 2025-2028 underscore not only the Asia-Pacific’s importance to Switzerland’s prosperity, but also Bern’s recognition of the region’s increasingly tense and complex strategic environment. A critical gap in this regard is the country’s limited academic expertise on Asia, which risks leaving decision‑makers without the depth of regional understanding needed in a fast‑moving crisis.

The Swiss response to a Taiwan war would depend on several aspects of the conflict: the scale of Chinese action, the unity of international response, and the EU’s position. If Brussels coordinated closely with Washington on a sanctions regime, the political cost of staying out would rise sharply. The Ukraine experience suggests that, under sufficient pressure, Switzerland is prepared to adapt neutrality to align with partners—but the economic and diplomatic weight of China makes this a more delicate calculation.

A partial alignment model could be strong enough to signal disapproval, but still be calibrated to limit damage to economic interests. Whether such a middle course would satisfy partners, or preserve Switzerland’s image as a principled actor, is another question. The war in Ukraine showed that Bern can adapt—but in a Taiwan contingency, the decisions would be harder and the costs higher. Switzerland can no longer count on keeping its economy detached from international geopolitical realities.

The main point: By forcing Bern to choose between its deep economic ties with China and its alignment with Western partners on democratic values and sanctions, a Taiwan conflict would pose a far greater challenge to Switzerland’s neutrality than the Ukraine war.