Lauren Dickey is a PhD candidate in War Studies at King’s College London and the National University of Singapore where her research focuses on Chinese strategy toward Taiwan.

On May 20th, former Taiwanese Vice President and Premier Wu Den-Yih (吳敦義) was elected as the next chairman of the Kuomintang (KMT) party with 52.24 percent of the votes. His win is an important turning point as the opposition party seeks to redefine itself. In terms of cross-Strait relations, it suggests a return to an outlook far more moderate than Hung Hsiu-chu’s (洪秀柱) blatant support for unification. Soon after the election was called, Wu’s comments suggested that respect for the so-called “1992 Consensus” and continued support for the peaceful development of cross-Strait relations is key for the KMT to win in Taiwan’s next round of local and presidential elections. Yet, given comments made by Wu both prior to and throughout his campaign, Beijing remains concerned that his centrist or pro-status quo outlook will slow, if not altogether impede, the development of cross-Strait relations in the PRC’s interest.

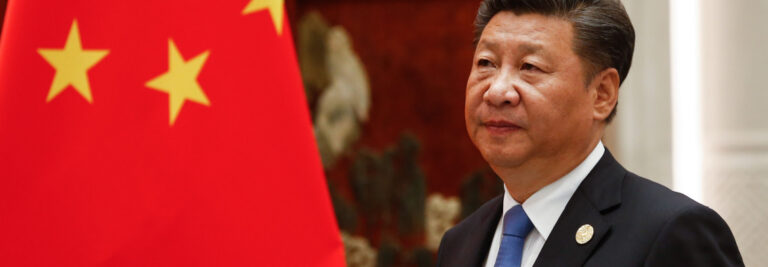

According to reports in Taiwanese media, as the election results became clear, Wu and the KMT waited in trepidation to receive a congratulatory message from Chinese president Xi Jinping. Both a symbolic olive branch between the KMT and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and a tradition that has continued uninterrupted since 1988, the telegraph from Xi arrived within 90 minutes. In it, Xi noted that peaceful cross-Strait development since 2008 has been enabled by the recognition of a common political framework. He urged the chairman-elect and the KMT to uphold the “1992 Consensus”—entitling each side of the Strait to their respective interpretations of One-China—and to commit to the opposition of Taiwanese independence. Xi voiced his hope that the two parties would prioritize the well-being of people on both sides of the Strait in sticking to the path of peaceful development and in jointly pursuing the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

In Wu’s reply, the chairman-elect echoed Xi’s wishes to carry forward peaceful, productive cooperation. He acknowledged that the KMT and CCP reached a “conclusion” in 1992 of adhering to the “One-China” principle, but emphasized the right to different oral interpretations of what “One-China” means. Although Wu had stressed that the KMT’s trajectory toward reclaiming political power in Taiwan required a respect for the “1992 Consensus,” in his reply to Xi, he did not explicitly accept the “1992 Consensus” as the cornerstone of cross-Strait relations. While Beijing officials may have been heartened to hear of Wu’s commitment to leading the KMT in ensuring the well-being of Taiwanese and deepening interactions across the Strait, his diplomatic maneuvering around the “1992 Consensus” immediately raised concerns in Beijing.

Beijing’s emphasis on “One-China” as the political foundation for KMT-CCP interactions was further elaborated by Taiwan Affairs Office (TAO) spokesperson An Fengshan (安峰山) on May 25. During the Q&A session, An was asked by several journalists about the implications of Wu’s election for the KMT and the CCP-KMT relationship. His remarks were— predictably – consistent with the content of Xi’s congratulatory letter to Wu. He elaborated upon the “1992 Consensus” as different oral expressions of the two sides of the Strait belonging to one China. Shared acceptance of the Consensus, An noted, would allow for intra-party cooperation amid cross-Strait relations otherwise belabored by current complexities (i.e., by President Tsai Ing-wen’s refusal to recognize “one-China”). His comments highlight the CCP’s preference for working with the KMT given its historically pro-China political agenda as contrasted to the outlook of the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP).

Beyond official media, those with whom the author has spoken in Beijing have been hopeful that Wu’s familiarity with officials on the mainland, and indeed, his experience working with former Taiwanese president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) on cross-Strait issues, will facilitate a smooth period of KMT-CCP relations. In 2012, Wu met Premier Li Keqiang (李克強) and then-TAO Director Wang Yi (王毅) at the Boao Forum in Hainan in his capacity as advisor to the Cross-Straits Common Market Foundation (兩岸共同市場基金會). According to press reports, his conversations with Wang and Li were characterized by mutual emphasis on the necessity of continuing the trends of peaceful development of the cross-Strait relationship. This recent history has led to many concluding that Wu will take a pragmatic stance on cross-Strait relations, not straying far from the “three nos”— no independence, no unification, and no war—of the Ma Ying-jeou era. In other words, as KMT chairman, Wu could seek to maximize benefits for the Taiwanese people by engaging with the mainland, but with little change to the political terms and conditions of the cross-Strait relationship likely.

Still others expressed their concern surrounding Wu’s election. His emphasis on the “different interpretations” clause of the “1992 Consensus” is widely interpreted as a warning signal. Moreover, unlike Hung who overtly supports unification with the the PRC, Wu sees both Beijing’s ambitions for unification under “one country, two systems” and Taiwanese pursuit of independence as destabilizing options. He has advocated for peace as the best choice for the Taiwan Strait at the present time. From Beijing’s perspective, this pro-status quo view has, however, been weakened by Wu’s remarks that any Taiwanese in favor of unification should move to the PRC rather than implicating 23 million Taiwanese in their efforts. As chairman-elect, Wu’s ambiguity about whether he will support the KMT’s status quo of developing cross-Strait relations or pursue an anti-unification agenda has thus fueled an initial perception on the opposite side of the Strait that he cannot be trusted.

In the words of one scholar-practitioner I spoke with in Beijing, the KMT under Wu is unlikely to be much different than the DPP: one seeks to maintain an independent Taiwan (the KMT), while the other aspires to achieve Taiwanese independence (the DPP). For now, Beijing can only wait and see whether Wu orients his policies toward the status quo in a manner reminiscent of Ma Ying-jeou, or if he seeks to more aggressively shift the KMT’s agenda toward formally preserving the separation across the Taiwan Strait. Beijing thus faces a decision between engaging with the KMT under Wu, consolidating the “1992 Consensus,” and deepening cooperation or, on the other hand, shunning the party altogether in response to a perceived agenda that threatens Beijing’s long-term goals of reunification and national rejuvenation.

The main point: From Beijing’s perspective, KMT chairman-elect Wu Den-Yih’s previous comments on cross-Strait relations are disconcerting and have nurtured a perception that he cannot entirely be trusted. Wu’s ambiguity on how the KMT seeks to manage the cross-Strait relationship presents a challenge to the status quo of intra-party engagement between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the KMT.