The Taiwan Strait is one of the world’s most dangerous flashpoints, and it will remain so for the foreseeable future. Beijing’s aggression toward Taiwan started decades ago, but the scale and intensity of its military provocations have skyrocketed in recent years. Incursions by Chinese aircraft into Taiwan’s air defense identification zone (ADIZ) have increased exponentially, and Beijing’s disproportionately large exercises following US Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s August 2022 visit to Taipei have fueled fears of a dangerous “new normal” in the region.

Responding to these developments, some prominent voices in Washington have warned that Beijing may attempt to invade Taiwan in the next few years. While they are right to be alarmed by the changing dynamics across the Taiwan Strait, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP, 中國共產黨) has no interest in fighting a war over Taiwan in the near-term. Though Beijing’s provocations dangerously increase the risk of conflict sparked by miscalculation or accidental escalation, the CCP is playing a long game and is not yet ready to back up its sovereignty claims with military force.

This article will introduce Beijing’s Taiwan policy and some of the key factors driving its likely approach to the island in 2023. An accurate understanding of these factors is important as Washington and Taipei seek to both manage escalation and counter Beijing’s long-term ambitions.

Beijing’s Policy and Approach

China’s behavior vis-à-vis Taiwan is rooted in both its long-term policy and its tactical approach to developments on the ground. The most authoritative statements of China’s Taiwan policy are outlined in official white papers (白皮書). The most recent of these was released in August 2022—notably during the period of heightened tensions immediately following Pelosi’s visit. Like the previous white papers from 1993 and 2000, it outlines a gradual plan for “peaceful reunification” (和平統一) under a “one country, two systems” (一國兩制) model. [1] Though refusing to renounce the use of force, the 2022 white paper calls this a “last resort” that would only be used if “separatist elements or external forces” crossed a red line. The document does not define Beijing’s red lines, but China’s Anti-Secession Law (反分裂國家法), released in 2005, indicates that these would include any actions to permanently separate Taiwan from China, or that Beijing believes would eliminate any possibility of “peaceful reunification.”

While China’s declared policy has remained largely consistent through the decades, its approach to Taiwan has fluctuated. The two biggest changes followed the election of the Kuomintang’s (KMT, 國民黨) Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) as Taiwan’s president in 2008, and current president Tsai Ing-wen’s (蔡英文) election in 2016. In the former case, Beijing ceased the hardline approach it had employed against Ma’s predecessors, inaugurating a period of unprecedented peace and cooperation that led some observers to erroneously conclude that Taiwan was no longer a military flashpoint. Tsai’s election had the opposite effect: despite her moderate stance toward the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Beijing fundamentally distrusts her and her Democratic Progressive Party (DPP, 民主進步黨), and responded to her election by reinstituting the previous confrontational approach.

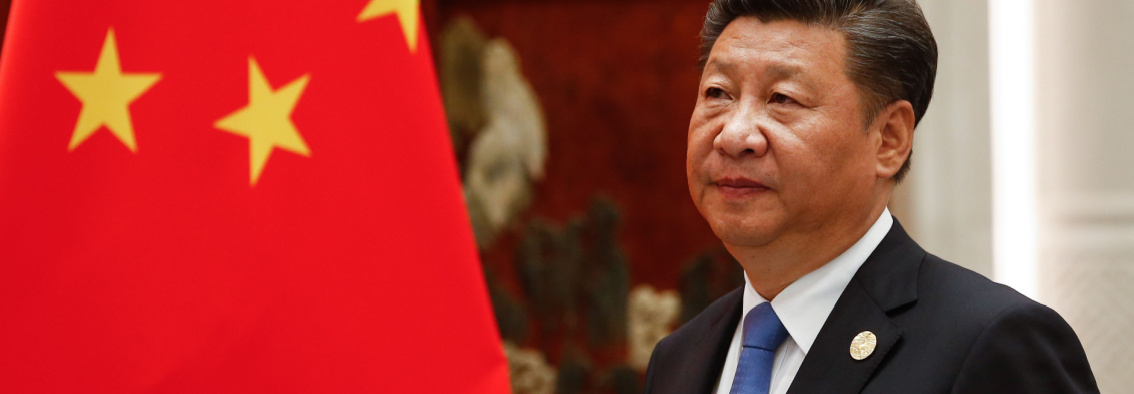

Many observers misunderstood these fluctuations as changes in China’s official policy. As shown above, however, the policy stayed the same. Furthermore, the timing of the changes corresponded with leadership transitions in Taiwan, not China—thereby contradicting the conventional wisdom that the different approaches reflected the preferences of the Chinese leaders who oversaw them. While personality differences likely played a role, former Chinese leader Hu Jintao (胡錦濤) oversaw a hardline stance against Ma’s predecessor Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) for years before easing tensions when Ma was elected. Hu’s successor Xi Jinping (習近平) continued this softer approach until Tsai became president. Xi even met with Ma in 2015, the first meeting between the leaders of the two sides in over six decades.

Drivers of Chinese Aggression

Understandably, many foreign observers have noted a discrepancy between the hardline tactics Beijing has employed since 2016 and the official policy outlined in its white paper. Beijing, however, views its actions as necessary for preserving the status quo and keeping alive the hope of “peaceful reunification.”

While there is no question that the CCP hopes to someday control Taiwan, it currently views the island not as an opportunity to be seized, but as a risk to be averted. China’s leaders are not under domestic pressure to seize Taiwan, but the nationalistic sentiment inspired by decades of intense propaganda messaging about the issue means that losing their claim over the island would jeopardize their legitimacy at home, and threaten their hold on power. This means that they cannot launch military action against Taiwan unless they are sure they will win—which is not currently the case, especially given their assumption that the United States would intervene on Taiwan’s behalf. It also means, however, that they would have to respond with force to any attempt to formally separate Taiwan from China.

Beijing’s military provocations aim both to placate nationalist voices in the PRC, and to deter Washington and Taipei from any action that would force the CCP to respond in order to preserve its legitimacy and hold on power. The CCP distrusts both the United States and the DPP and fears they are moving closer to such action, which would necessitate a military response. Even if successful, such a war would destroy much of China’s military, derail its “great rejuvenation” (偉大復興), and jeopardize its ability to secure its heartland against foreign and domestic threats.

This is not to disregard the threat Beijing poses, but rather to put the threat into its proper long-term context. The CCP views China’s rise and the United States’ decline as almost inevitable. It believes that, if it can continue avoiding major military conflict until the power balance has shifted indisputably in China’s favor, it will eventually be able to take Taiwan, preferably without firing a shot.

What to Expect in 2023

As usual, Beijing’s approach to Taiwan in 2023 will be driven mostly by domestic considerations in the PRC, primarily concerns around the CCP’s legitimacy. It will also seek to manage risks and seize opportunities related to Taiwanese politics—in particular the island’s presidential election in January 2024, which will have important implications for Taiwan’s China policy. Both drivers will make it hard for Beijing to moderate its aggressive stance toward the island, but they will also make the CCP extra careful not to let tensions spiral out of control.

Domestic Legitimacy Crisis

Heading into 2023, the CCP leadership are facing their worst legitimacy crisis since the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre. The failure and abrupt abandonment of the zero-COVID policy—upon which Xi and the CCP had based much of their claim to legitimacy since 2020—left a disillusioned, under-vaccinated public and a healthcare system unprepared for the crisis that China’s own studies had warned would result. Meanwhile, China faces its worst economic challenges in decades, with the real estate sector in crisis and youth unemployment hitting record highs. While the CCP will almost certainly survive these crises, they will dominate the focus of senior leaders such as Xi for at least the first few months of the year.

Some speculate that Beijing might seek to distract the Chinese public from these domestic challenges through a “diversionary war” against Taiwan. This is highly unlikely, given the impact a failed attempt to take the island would have on Xi’s already damaged legitimacy. It is more likely that the Chinese leadership are so preoccupied with their domestic challenges that they will be especially careful to avoid any crises outside the PRC.

Indeed, Beijing not only lacks a history of engaging in diversionary conflict, but it appears to be more aggressive abroad when the regime is strong domestically and more cautious when it faces significant internal challenges. [2][3] Since the current crises hit in late 2022, Beijing has moderated its diplomatic style and sought to reset its relationships with foreign countries. This change in tone has been so noticeable that some speculate that China is abandoning its abrasive “wolf warrior diplomacy.” While this softening is likely only a short-term tactic, it indicates that Beijing’s challenges are making it less, and not more, aggressive. China has a particular interest in improving its relationship with the United States. The state of this relationship is a black mark on Xi’s record, and given that the Taiwan Strait is the most sensitive issue in this bilateral relationship, Beijing must manage the tensions carefully to have any hope of détente.

Taiwan’s Elections in 2024

Taiwan’s presidential and legislative elections are scheduled for January 2024, and Beijing views its role as important for helping bring about what it views as the least concerning outcome: a KMT victory. In addition to deterring any moves toward independence, China’s hardline stance also aims to delegitimize the DPP. Though the CCP and KMT are historical enemies and the KMT rejects Beijing’s unification model, China trusts that the KMT will not seek formal independence.

Beijing believes its approach these past seven years has been effective. Tsai has consistently opposed moves toward independence, and the KMT defeated the DPP in the last two local elections (2018 and 2022). Furthermore, a year ahead of the presidential election, some opinion polls show the most likely KMT candidate winning. While it is not clear what role, if any, China’s pressure tactics have played in these developments, they have not hurt its cause and are unlikely to be scrapped before the election.

The CCP will be careful to keep its provocations within bounds, however, to avoid inadvertently helping the DPP. Tsai recovered from devastating DPP losses in the 2018 local elections to win reelection in 2020, in large part by capitalizing on China’s suppression of the Hong Kong protests. Though Taiwan’s elections are mainly driven by domestic issues and Tsai also benefited from a controversial KMT opponent, that year the China threat played an outsized role, and Beijing does not want this to happen again in 2024.

The main point: China’s approach to Taiwan in 2023 will broadly follow the confrontational stance it has employed since 2016, but it will be careful not to let tensions spiral out of control. Beijing remains committed to a long-term process of “peaceful reunification,” and views its pressure as important for preserving the CCP’s claim over Taiwan—and its own regime legitimacy—while avoiding a military conflict it is not yet prepared to fight.

[1] “One country, two systems” is the model under which Hong Kong and Macau maintain their own separate political and economic systems but are under the ultimate sovereignty of Beijing. China first developed the model in 1979 as a proposal for unification with Taiwan.

[2] Quantitative studies have not found a correlation between internal unrest and external aggression. See M. Taylor Fravel, “International Relations Theory and China’s Rise: Assessing China’s Potential for Territorial Expansion,” International Studies Review 12 (2010): 521. http://web.mit.edu/fravel/www/fravel.2010.ISR.china.expansion.pdf

[3] In one case in point, Beijing’s tendency during the pandemic has been to be less aggressive when it faces significant outbreaks (January-March 2020 and December 2022-January 2023), and more aggressive when it has the virus under control (especially April 2020-early 2022).