Prior to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and Beijing’s decision in July 2019 to restrict individual tourist travel to Taiwan, cross-Strait maritime passenger transportation ties were rapidly advancing. At the same time, however, cross-Strait maritime cargo traffic was stagnating [see Table 1]. The pandemic has upended this growing dichotomy: since the outbreak of the virus, cargo traffic between China and Taiwan has steadily grown, while cross-Strait maritime passenger traffic remains suspended at Taipei’s behest. Looking to the future, China has upped its investments in maritime transportation and attendant infrastructure—especially in Fujian Province, which is located opposite Taiwan—to promote “cross-Strait integrated development.” Due to Fujian’s strategic location opposite Taiwan, the province has played a leading role in fostering cross-Strait transportation connectivity. If Taipei and its partners want to ensure that Taiwan does not become too economically reliant on China, more attention and resources may be needed to enhance the island’s maritime connectivity.

Cross-Strait Maritime Transportation

In 2019, 2.269 million passengers used direct maritime routes to travel between the People’s Republic of China (PRC or China) and the Republic of China (ROC or Taiwan)—including the offshore islands of Kinmen, Matsu and Penghu—an increase of 4.2 percent over the previous year. By contrast, cross-Strait maritime cargo tonnage dipped 5.5 percent year-on-year to 48.35 million tons, while container volume increased 1.8 percent year-on-year to 2.505 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU). [1]

|

Table 1: Cross-Strait Cargo and Container Throughput & Passenger Traffic |

|||

|

Year |

Cargo Throughput (millions of tons) |

Container Throughput (millions of TEU) |

Maritime Passengers (millions of passengers) |

|

2021 |

52.4 |

2.414 |

0 |

|

2020 |

51.92 |

2.368 |

0.104 |

|

2019 |

48.35 |

2.505 |

2.269 |

|

2018 |

50.22 |

2.22 |

2.154 |

|

2017 |

49.92 |

2.25 |

1.971 |

|

Source: Data from the PRC’s Ministry of Transport |

|||

Up until Beijing prohibited the issuance of travel permits for individual Chinese tourists to visit Taiwan, maritime passenger transportation between the PRC and the ROC was experiencing robust growth. Despite the deterioration of cross-Strait relations following the election of Taiwan’s president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) in 2016, the two sides had proceeded to increase cross-Strait ferry services, even establishing a new route between Pingtan (Fujian Province) and Kaohsiung (Taiwan) less than a month before China announced its new travel restrictions.

China’s cross-Strait cruise industry was also on the mend in 2019. A cruise line from Xiamen (Fujian Province) to the ROC’s Penghu Islands and Kaohsiung temporarily resumed operation in May 2019. (The route had been suspended since July 2016.) Chinese officials implied that the resumption of cruises was linked to the outcome of Taiwan’s November 2018 local elections and increasing expressions of support for the so-called “1992 Consensus” (九二共識) by Taiwanese “counties and cities.” The then-newly elected mayor of Kaohsiung Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) and the newly elected magistrate of Penghu County Lai Feng-wei (賴峰偉) had by then come out as proponents of closer cooperation with Beijing, and Han had expressed his support for the “1992 Consensus” on multiple occasions.

Starting in January 2020, China began limiting cross-Strait passenger ferry service to fight the spread of COVID-19. On February 2, 2020, Chinese state media reported that passenger ferry service between Fujian Province and Kinmen and Matsu would be reduced due to the virus. Days later, Taiwan’s Central Epidemic Command Center (CECC, 國家衛生指揮中心中央流行疫情指揮中心) announced that all PRC nationals would be temporarily prohibited from entering Taiwan as a precaution against the emerging pandemic.

While cross-Strait maritime passenger traffic has plummeted as a result of the pandemic, cargo transportation has weathered the crisis well [see Table 1]. In the case of Fujian Province, its maritime cargo transportation ties to Taiwan have deepened considerably since 2019. Following a steep decline in Taiwan exports/imports throughput at Fujian coastal ports in 2019, the province experienced a swift rebound, with throughput figures approaching 2018 levels by 2021.

Over the last several years, a number of shipping lines between China and Taiwan have been established or expanded. In October 2020, local Chinese officials presided over the launching of the Fuzhou Mawei (Fujian Province)-Taiwan cross-border e-commerce goods direct shipping line. A year later, local customs authorities reported the inauguration of a new container shipping line between Pingtan and Taipei. This new line greatly supplemented the services of a pre-existing line by utilizing a significantly larger ship and increasing the frequency of voyages between Pingtan and Taipei from three a week to six.

Intermodal Transportation

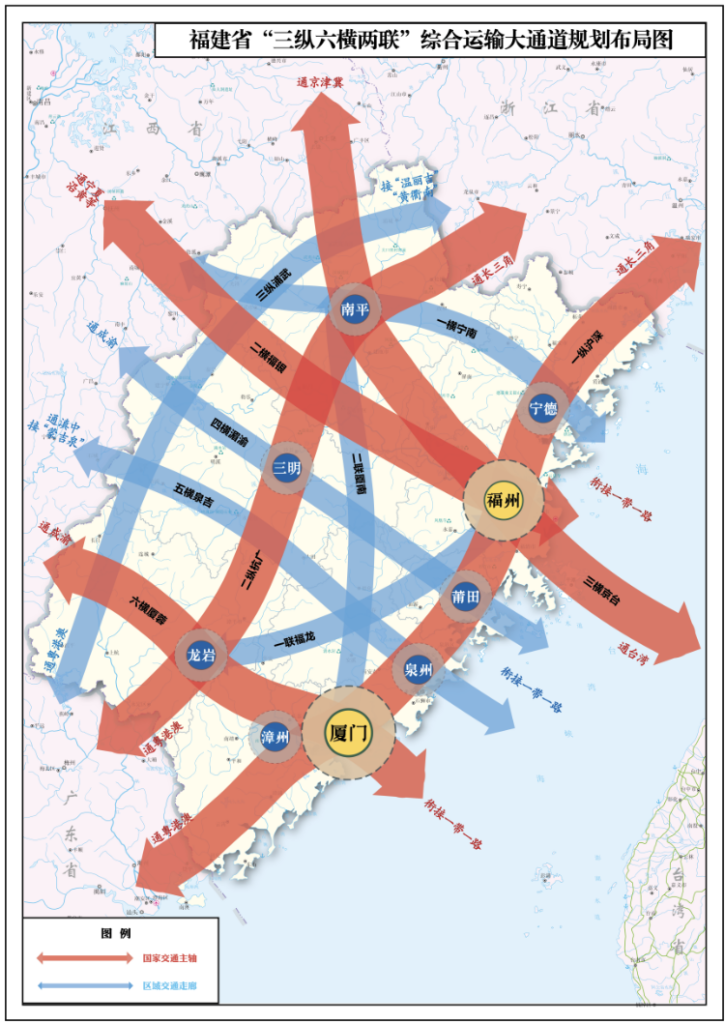

The PRC has long endeavored to construct a national transportation system that integrates Taiwan, first through maritime and air linkages, and ultimately through bridges and tunnels. Due to Fujian’s strategic location opposite Taiwan, the province has played a leading role in fostering cross-Strait transportation connectivity. Many national and provincial transportation routes have converged on Xiamen and Fuzhou (including Pingtan) to support trade and travel between the PRC and the ROC [see Figure 1]. In fact, this duty now falls under Fujian’s broader responsibilities as a “Core Area of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road”.

In recent years, China’s capacity to move goods and people across the Taiwan Strait via “intermodal transportation” (聯運) has been enhanced by the development of infrastructure in and around the two major port cities. In November 2015, China opened the Taiwan-Pingtan-Europe sea-rail line, which utilizes a ferry to transport goods from Taiwan to Pingtan before shipping them to Europe by train. A similar Taiwan-Xiamen-Europe sea-rail line commenced operation in April 2016. The first shipment of goods along a new intermodal line from China’s Jiangxi Province to Taiwan reached its maritime embarkation point at Xiamen Port in mid-January 2022. China launched yet another new intermodal line, the Taiwan-Xiamen-St. Petersburg sea-rail line, in June 2022 (purportedly in response to difficulties with maritime transportation to Russia in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine). China has also worked to create sea-air intermodal transportation channels. One such line connecting the ROC’s Taoyuan International Airport to Pingtan via ferry service from Taipei began operating in November 2016.

Since the start of the pandemic, China has also completed major infrastructure projects in Fujian that it sees as beneficial to cross-Strait integrated development. Many of these projects correspond with official policy promoting cross-Strait intermodal transportation. For example, the Pingtan Strait Road-Rail Bridge, which connects the island to the PRC’s national integrated transportation system by highway and high-speed rail, officially opened in December 2020. The bridge is intended to boost cross-Strait travel.

Fujian provincial authorities have placed a heavy emphasis on cross-Strait infrastructure connectivity and maritime transportation in their current transportation development plans. Additionally, they have raised the province’s investments in transportation infrastructure well above pre-pandemic levels, improving Fujian’s capacity to handle cross-Strait trade and passenger traffic.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development)

Conclusion

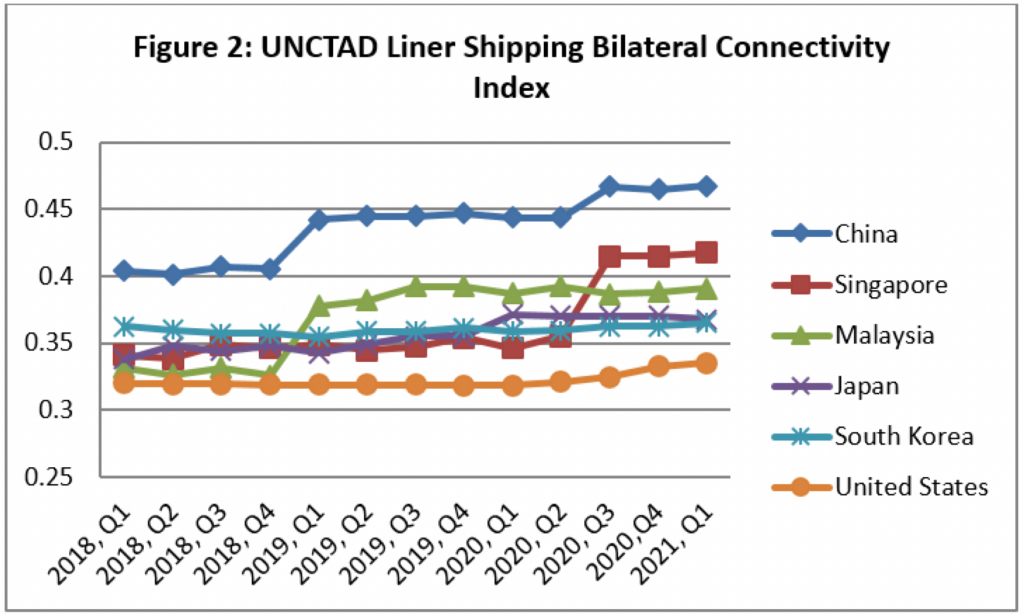

Despite the global disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, China’s efforts to deepen cross-Strait maritime cargo transportation ties have borne fruit. Since the start of the pandemic, China-Taiwan maritime connectivity, as measured by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s Liner Shipping Bilateral Connectivity Index, has increased [see Figure 2]. The continued growth in cross-Strait maritime connectivity has helped China maintain its position as far and away the most “connected” country to Taiwan—even as Taiwan has been working in recent years to reduce its relative reliance on China as a trading partner.

Nonetheless, the ROC has also deepened its domestic and international maritime connectivity. It opened a new high-speed ferry service between Taiwan and Matsu in April 2022, which has cut the sea travel time between the islands from 10 hours to 3 hours. And a ferry that had serviced cross-Strait travel before the pandemic has since been repurposed to transport passengers between Tainan, Taiwan and the Penghu Islands.

In August 2021, the ROC’s National Development Council approved a plan to invest US$ 1.37 billion to upgrade seven of the country’s international commercial ports. Taiwan’s international maritime ties have also been boosted by Beijing’s restrictions on certain Taiwan products, which have forced some Taiwan producers to reroute their goods to other markets. Seeking to further bolster Taiwan’s regional maritime relations, Taiwan and Philippine officials signed a “Memorandum of Understanding on Maritime Cooperation” in February 2022. But Taiwan’s largest trading partners have seemingly been more focused on working with Taiwan on maritime security issues than on investing in maritime connectivity. And Taiwan’s capacity building at home and with its partners pales in comparison to the progress China has made on the other side of the Strait, by doing such things as upgrading port capacity to facilitate iron ore transshipments to Taiwan and steadily increasing its cross-Strait shipping lines.

New cross-Strait shipping lines, investments in China’s transportation system, and improvements in customs clearance processes have made cross-Strait maritime transportation ever more efficient. Fujian’s proximity to Taiwan has made it the most important PRC province for facilitating cross-Strait e-commerce and maritime express trade. As of October 2021, Pingtan Port alone processed 60 percent of PRC cross-border e-commerce exports to Taiwan.

It is possible that current tensions between the PRC and the ROC will lead Taipei to maintain restrictions on cross-Strait maritime passenger transport for quite some time. Even before China’s August military exercises around Taiwan, the ROC Mainland Affairs Council (MAC, 大陸委員會) indicated that the administration was taking into consideration more than just the pandemic in its decision on when to reopen cross-Strait maritime travel. Furthermore, ROC-PRC maritime trade will likely not greatly exceed its recent growth rates for the remainder of ROC President Tsai’s term in office.

However, more than a few ROC politicians have expressed their desire for Taiwan to participate more actively in Beijing’s cross-Strait integrated development projects. In the past, some ROC politicians have even supported the idea of building an “economic circle” with China, an idea very similar to Beijing’s concept of cross-Strait integrated development. If Taiwan were to elect such a political figure as president of the ROC in 2024, Beijing might be able to more fully capitalize on the investments it has made in maritime transportation capacity. The pandemic has provided an opportunity for Taipei to recalibrate its approach to cross-Strait maritime transportation ties.

The main point: China has continued to plan and push for deeper cross-Strait maritime transportation ties since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. If Taipei and its partners want to ensure that Taiwan does not become too economically reliant on China, they may need to devote more attention and resources to enhancing their own maritime connectivity.

[1] According to Flexport, “A TEU (twenty-foot equivalent unit) is a measure of volume in units of twenty-foot-long containers. One 20-foot container equals one TEU.”