Following a classified briefing on February 9 with military and intelligence officials, Republican senators reportedly expressed concern that US manufacturing may have inadvertently contributed to the Chinese spy balloon that recently violated US air space (as well as similar balloons that have overflown other countries in the Asia-Pacific region). According to a source familiar with the briefing, components in the Chinese balloon had Western-made parts and English writing.

Others have previously expressed similar concerns about Western and allied technology ending up in Chinese weapons. Back in 2019, US officials warned Taiwanese diplomats that Huawei (華為) was using Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC, 台積電)–built semiconductors in Chinese missile guidance systems aimed at Taiwan. In 2021, a Washington Post story also reported that the Chinese company Phytium Technology Co. (飛騰) was using TSMC chips in advanced Chinese military systems, to which Taiwan Minister of Economic Affairs Wang Mei-hua (王美花) responded that “to the best of our knowledge” the Chinese military was not the intended end-user for any of TSMC’s chip exports.

Nonetheless, Ou Si-fu (歐錫富), a research fellow at the Institute for National Defense and Security Research (INDSR, 國防安全研究院) in Taipei, has pointed out challenges associated with imposing export controls on semiconductors: “The problem is that the chips are dual-use technology,” and as such, “they can be bought off the shelf for one application and then used in military equipment that is aimed right back at Taiwan.”

This issue is at the heart of the dilemma currently facing policymakers in the United States, Europe, and Asia: how can governments maintain national security in the face of increasingly globalized, interlinked defense and industrial sectors? Driven by the desire to maintain—or acquire—production capabilities in key military-related industries, governments often inject national security considerations into discussions of economic management. Since threats to such supplies contribute directly to military capability, these sorts of economic threats have essentially become military threats.

The semiconductor industry, by virtue of the dual-use applications of its products and critical role in national defense industrial bases, has both major economic and military significance that give it an outsized role in the emerging geopolitical competition between the United States and China. Continued advancements in Taiwan’s semiconductor sector—to include the construction of major new research and development (R&D) and manufacturing facilities in southern Taiwan—are likely to further reinforce Taiwan’s leading role in this critical industry.

“Strategic Industry”: Rationales for State Intervention in the Semiconductor Sector

Besides the dual-use characteristics of many semiconductor products, the broader semiconductor industry is also viewed as a “strategic” or “critical industry” due to its vital role in a modern economy. The chip industry is considered particularly “strategic” due to its linkages to the rest of the economy, and the possibility of monopoly profits in this sector. Furthermore, the relatively fixed sunk cost of R&D and capital equipment investments, and the decreasing unit costs with improved yields, create “first mover advantage,” in which a privileged position in one market can create scale economies over rivals and capture more technological externalities (positive externalities) in future generations of semiconductor products. [1]

The linkage argument is best illustrated by the electronics “food chain” theory, in which upstream and downstream industries’ competitive fortunes are interlinked in a complex ecological system that makes each dependent on the health of the others. [2] As witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic and resultant chip shortages, damage to the chip sector caused the German automotive industry to suffer losses, culminating with then-German Minister of Economic Affairs and Energy Peter Altmaier writing to his Taiwanese counterpart Wang Mei-hua to encourage TSMC to ramp up production. When there was a shortage in the component level of advanced (e.g., smaller than 10 nanometer) chips from TSMC, this also posed a serious risk to other high-tech sectors, as these products are crucial inputs in smartphones, computers, and military and space equipment.

Many industries employing semiconductors are considered integral to national security, and are typically deeply connected to national defense. Given these considerations, such industries are often subject to considerable government oversight and intervention. Furthermore, since it can cost more than USD $20 billion to build a new chipmaking plant, the list of leading-edge firms capable of manufacturing at scale has essentially been reduced to three: TSMC, Intel, and Samsung. This short list makes each company that much more important.

Image: Local Tainan City officials at the inaugural ceremony for opening the “ITRI Compound Semiconductor Southern Development Base”—one of the links in the “Southern Semiconductor S Corridor” that will expand semiconductor production in southwestern Taiwan. (Image source: Tainan City Government)

“Chip Wars” and the Enduring Importance of Taiwan

Given the importance of the sector, it is not surprising that the semiconductor industry has been characterized by repeated US Government interventions: first during the chip war with Japan in the 1980s, and now with China in the 2020s. The 1980s was characterized by greater integration of the commercial and defense sectors, and the globalization of an increasingly commercial defense industrial base. At the same time, the Japanese semiconductor industry emerged as a major force in the world market. By 1985, Japan’s share of the global market for Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) chips had surpassed the United States, with Washington accusing Tokyo of dumping chips in an effort to cripple the US industry. The trade friction was exacerbated by comments from an ultranationalist member of the Japanese Diet, Shintaro Ishihara, who threatened to cut off semiconductor supplies to the United States and sell them to the Soviet Union instead. Eventually, amid rising concerns about defense dependence on foreign—especially Japanese—sources of supply, US policymakers established SEMATECH in 1987—a joint government-industry consortium intended to revitalize the US domestic semiconductor manufacturing industry.

Now history is being repeated in the ongoing US-China “chip war.” The United States has spearheaded the establishment of the “Chip 4” alliance—with partners Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan—in order to ensure a resilient semiconductor supply chain. The American Institute in Taiwan (AIT) hosted the first virtual meeting of the group on September 28, 2022. Notably, Taiwan’s TSMC plays a key role in this alliance, given its near-monopolistic 92 percent of market share for advanced semiconductors. Given the US Department of Defense’s growing need for a secure and reliable chip supply, reshoring semiconductor manufacturing capability is at the top of the US agenda. The new TSMC chipmaking facility in Arizona is one example of these efforts.

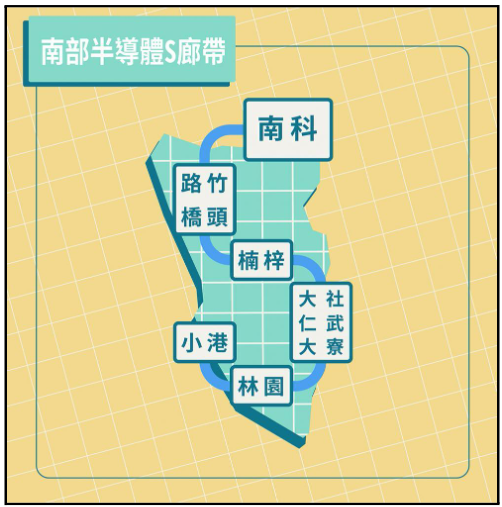

Image: A diagram depicting the existing or planned facilities that will form the “Southern Semiconductor S Corridor” between Tainan and Kaohsiung—a group of facilities intended to further advance semiconductor production in southern Taiwan. (Image source: Kaohsiung City Government)

The “S Corridor” and Taiwan’s Role in Supply Chain Security

Besides reshoring, TSMC in Kaohsiung is also playing an important role in Indo-Pacific supply chain regionalization. To that end, Nanzih Technology Industrial Park will become the core zone of Taiwan’s “Southern Semiconductor S Corridor” (南部半導體S廊帶)—a policy priority envisioned by Kaohsiung Mayor Chen Chi-mai’s (陳其邁) administration, which is intended to establish a new technology industrial cluster in southern Taiwan (centered around the greater Kaohsiung area). The project will “connect Tainan Science Park, Renwu Industrial Park, Ciaotou Science and Technology Park, and Nanzih Technology Industrial Park” in an S-shaped corridor. Besides TSMC, the project has already attracted other major technology companies such as Win Semiconductors Corp, the Netherlands-based NXP, and the Germany-based Merck Group. Furthermore, Nanzih Technology Industrial Park is already home to Taiwan’s second largest semiconductor company, Advanced Semiconductor Engineering (ASE, 日月光半導體製造股份有限公司). In August 2022, TSMC held a groundbreaking ceremony for their new plants in Nanzih, which are slated to first produce 28 nanometer chips used mainly in the automotive industry, as well as seven nanometer chips in the near future.

Nonetheless, it is important to point out that US-China trade friction in semiconductors does not necessarily mean a decoupling from China’s economy, but rather a selective diversification and remapping of the high-tech supply chain. China remains a top trading partner for Taiwan and other allies such as Japan and South Korea, and as Taiwan’s Deputy Economic Affairs Minister Chen Chern-chyi (陳正祺) has observed, “I don’t see [how] we can completely decouple from China. That’s not realistic.” Moreover, as Major Jessica Taylor and Jonathan Corrado argued in a recent article in The National Interest, due to the globalized nature of the chip supply chain, decoupling would be expensive and could potentially alienate US partners, as well as inhibit the innovative capacity of US companies. Thus, at this juncture, the “Chip 4” alliance seems to be a prudent way forward to build resilience in the supply chain, as policymakers in Taiwan, the United States, and allied countries continue to balance the trade-off between maintaining national defense and innovation in an increasingly globalized industrial sector.

The main point: Given TSMC’s near monopolistic position in production of advanced semiconductors, Taiwan is a linchpin in supply chain security for the United States and its allies—and the construction of new facilities for semiconductor production in southern Taiwan will further reinforce Taiwan’s importance in this industry.

[1] In general, a strategic industry is one characterized by high entry barriers, first-mover advantages, high sunk costs, and externalities. As noted in the early 1990s by analyst Laura D’Andrea Tyson, high research and development (R&D) expenditures and steep learning curves create entry barriers for firms lacking sufficient capital, and encourage them to develop “technology drivers”—“a high-volume product with a relatively simple design.” In doing so, such firms may “hone [their] manufacturing skills and transfer [their] learning to more complicated, lower volume, high value-added devices.” See: National Advisory Committee on Semiconductors (NACS), A Strategic Industry at Risk: A Report to the President and the Congress (Washington, DC: 1989); and Laura D’Andrea Tyson, Who’s Bashing Whom? Trade Conflict in High-Technology Industries (Washington, DC: Institute of International Economics, 1992), 89.

[2] NACS, Strategic Industry at Risk, 9.