With rising cross-Strait tensions, news stories—and misinformation—about Taiwan’s National Palace Museum (NPM, 國立故宮博物院) have often emphasized its status as a cultural flashpoint in the relationship between Taiwan and China. The points of controversy have ranged from discussions of evacuation strategies to protect museum collections in the face of a Chinese invasion, to broken artifacts igniting outrage from Chinese netizens, and—just last month—digital images leaked from the NPM ending up for sale on Taobao (淘寶).

These incidents are notable for illuminating the importance of museums in preserving as well as promoting a shared historical memory and identity. However, solely focusing on the NPM’s Chinese origins and its significance for both China and Taiwan risks minimizing the role of Taiwan’s museums in contributing to alternative perspectives of Taiwanese identity. Notably, over the past two decades, Taiwan’s cultural policy—particularly under the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP, 民主進步黨)—has sought to redefine Taiwanese identity as one that is more diverse, presenting Taiwan as a “multicultural society.”

Curating Taiwan’s Identity

Comparing the origins of the NPM, the National Taiwan Museum (NTM, 國立臺灣博物館), and the National Museum of Taiwan History (NMTH, 國立臺灣歷史博物館) provides excellent examples of how governments have used museums to complement their broader political and cultural agendas.

Established in 1908, the NTM is the oldest museum in Taiwan. Intended to “commemorate the opening of the west coast railway,” the NTM was designed by two Japanese architects, built by a Japanese company, and was a “symbol of Japanese colonial achievement.” To this day, the NTM remains the only museum built during the Japanese colonial era of Taiwan open at its original site. Despite this background, the permanent exhibition at the museum now focuses on the history of indigenous people in Taiwan.

Following the arrival of the Kuomintang (KMT, 中國國民黨) in Taiwan, cultural policies favored a national identity that emphasized the Chinese ethnic heritage of many Taiwanese. The NPM, full of what some consider to be the most valuable parts of China’s Palace Museum collection, served to assert the KMT’s legitimacy as the sole legitimate Chinese government, as well as to educate local Taiwanese about their Chinese heritage.

In the years since the lifting of martial law in Taiwan, NPM has sought to expand and modify its image—first by opening the Southern Branch of the National Palace Museum (NPMSB, 國立故宮博物院南部院區) in 2015, and then stating its intention in 2017 to show its visitors “art and culture through the lens of [a] pan-Asia or pan-Taiwan, instead of a China-centric view.” Despite these changes, Taiwanese youth still often view the NPM as “mired in the past,” and more representative of China’s legacy than of Taiwan’s own history.

By contrast, the NMTH—founded in 2011—was one of the first museums to be established after Taiwan’s democratization. In line with recent cultural policies that stress the multicultural character of Taiwan, NMTH aims to “[consist] of multiple dialogues that shape the cultural subjectivity, civil society, and cultural diversity of Taiwan.” Unlike the NTM and NPM, visitors to the NMTH are invited to not only participate in the exhibitions, but also help create them. Adopting a bottom-up approach to its curation, NMTH allows visitors to the museum to actively contribute to its exhibits, with roughly a third of its collection of 150,000 artifacts donated by the public.

Greater public participation is a positive step for Taiwan’s nation branding. Grassroots depictions of Taiwan provide more nuance and give agency to the public in shaping the country’s image. Furthermore, such depictions are also “more likely to strike an emotional chord.” Another benefit to a more multicultural and open approach is that rather than rewriting history into a new dominant narrative, prior narratives can be reframed as part of that diverse Taiwanese identity. This is evident in the description for a joint exhibition held between the NTM, the NPM, and the NMTH, stating that the three museums “reflect the history and material culture of the three main players in Taiwan’s history: the indigenous people (NTM), Han Taiwanese (NMTH), and the Chinese imperial court and officials (NPM).”

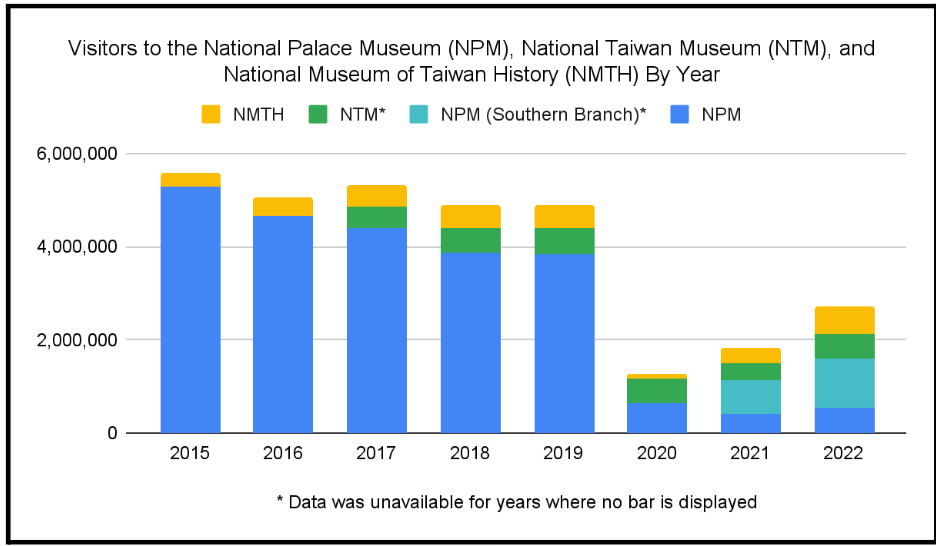

Graph: Visitors to NPM, NTM, and NMTH by Year. (Graph by author. Data from: Taiwan Tourism Bureau, MOTC)

Still, even if Taiwan finally has a coordinated strategy to bring these museums together into an overarching identity, how many people actually get to experience these exhibits? While visitors to the NPM were high prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, numbers have decreased precipitously in the years since, and it remains to be seen whether the attendance levels will return to what they once were. Therefore, to expand their reach and combat the effects of COVID-19, Taiwan’s museums should pursue other methods of international engagement. In doing so, they could contribute a great deal to updating Taiwan’s national image abroad.

International Outreach

Digitization

In the wake of COVID-19, going virtual could be one way of expanding Taiwan’s reach to other countries. In 2016, Academia Sinica (中央硏究院) introduced the Open Museum (開放博物館) platform to promote digital transformation. Through the platform, museums, archivists, and private collectors can store, view, and curate uploaded collections. From 2020 to 2022, in lieu of museum closures and travel restrictions, Open Museum held virtual events on International Museum Day, allowing visitors access to museums around the world. The 2022 event featured 18 overseas museums and libraries, as well as 43 domestic museums and institutions, including international museums such as The Cleveland Museum of Art and the Tokyo National Museum. In addition to collections hosted on the Open Museum website, many Taiwan museums and institutions—such as Art Bank Taiwan (managed by the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts), the NTMH, and the NPM—have online exhibitions and digital archives of their collections available on their websites.

This move towards digitization, which even began pre-COVID, is an excellent example of how Taiwan has been able to increase the accessibility of museum collections and promote collaboration between researchers. However, the fact that the Open Museum website, along with many of the digital museum databases, is only offered in Chinese limits its usefulness for foreign audiences. Still, even if the platform itself is not used directly as a method of international outreach, the skills behind these digitization processes could nevertheless serve as a foundation for future exchanges.

Memoranda of Understanding and Exchange

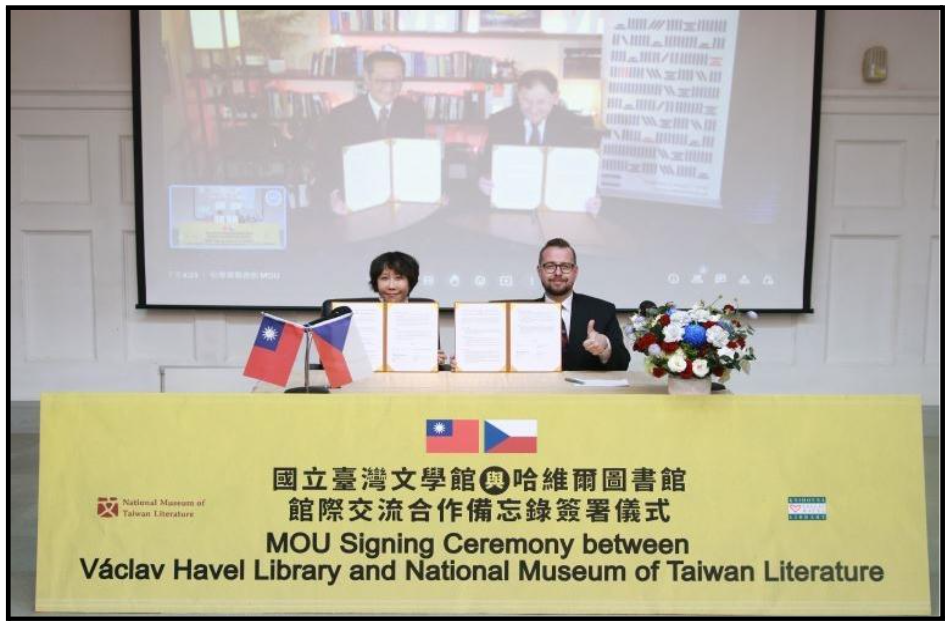

Cooperation on physical exchanges is another way to help Taiwanese museums bring their exhibitions abroad. On February 6, Taiwan’s National Museum of Taiwan Literature (NMTL, 國立臺灣文學館) signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with Václav Havel Library (VHL) in the Czech Republic. Aiming to increase mutual understanding between the two countries, the NMTL and the VHL agreed to exchange exhibitions, with the Taiwanese exhibition focusing on “a wide range of themes such as transgender [identity] and ethnicity, fully demonstrating the island’s diversity, vibrancy, and openness.” Considering that subnational relations are underutilized in Central Eastern Europe (CEE)-Taiwan ties, this MOU is a positive step towards increasing understanding between CEE states and Taiwan, which could in turn contribute to positive trends of opinion between the two regions.

In addition, cooperation between the two countries also presents an opportunity for participants to learn from each other. The two institutions announced that they would collaborate on an exchange program for experts of their institutions, as well as publishing and professional training programs. VHL Executive Director Michael Žantovský also mentioned that the VHL was interested in learning digitization techniques from Taiwan experts, suggesting that Taiwan can also use its digital advancements as a basis for cooperation in training and professional programs.

Image: MOU signing ceremony between the NMTL and Václav Havel Library (Image Source: Ministry of Culture Website)

Leasing Exhibitions

Even without an MOU or a framework for reciprocal exchange, Taiwanese works can also be leased for display. For instance, Taiwan’s Ministry of Culture (MoC, 文化部) developed the Art Bank Taiwan (藝術銀行) project in 2013 to help finance local artists and introduce Taiwanese art to foreign audiences by securing exhibition spaces (domestically and overseas) and loaning art to government agencies. With an annual budget of USD $2.4 million, Art Bank Taiwan purchases art from emerging artists and has regular open calls for new artwork submissions, during which any Taiwanese citizen is eligible to submit their artwork for consideration. Currently, the Art Bank is in possession of more than 2,921 contemporary Taiwanese artworks, and their digital collection of works is maintained by the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts (NTMoFA, 國立臺灣美術館). Additionally, many of these works can be viewed online through exhibitions in English.

Art Bank Taiwan also partnered with Taiwan’s Ministry of Transportation and Communications (交通部) to put artwork in locations such as Taoyuan International Airport and Kaohsiung International Airport, in addition to reaching out to the private sector. However, their clients are still primarily Taiwan-based corporations. To bring Taiwanese art abroad, the MoC and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA, 外交部) had their first joint collaboration in 2017, when the Taipei Representative Office in Singapore hosted art loaned from Art Bank Taiwan. In the years since, Art Bank Taiwan has held exhibitions in New York, London, and Washington, among others. Yet, many of these exhibitions are still held at Taiwan’s representative offices—in part due to pressure from China that limits Taiwan’s ability to use its own name in exhibitions abroad. In the future, to allow Taiwanese art to be viewed by wider audiences, exhibitions by Art Bank Taiwan will hopefully be able to graduate from being hosted in purely Taiwan-owned locations, to taking up residence in overseas locations that are more integrated domestically and will be more widely attended by foreign populations.

Conclusions

Considering the important role that museums, art, and cultural artifacts can play in allowing other countries to learn about a nation’s identity, it will be important for Taiwan to think about not only curating its image domestically, but also how that image can be shown to the international world. This is especially crucial for Taiwan, as such exhibitions are often seen as “neutral” ways for countries to connect. Accordingly, they could serve as a way to increase international understanding of how Taiwan views itself and its own history.

Taiwan has already begun the process of displaying a more updated and inclusive Taiwanese identity in its museums. Foreign countries can help support Taiwan’s growth in this regard in a number of ways, including: directly consuming Taiwanese exhibitions online through Open Museum and other museum websites; pursuing agreements and MOUs to co-host exhibitions or host training exchanges; and leasing exhibitions from Taiwanese institutions such as Art Bank Taiwan. Through these methods, the international community can help promote more modern images of Taiwanese identity and allow Taiwan to control more of its narrative—which the People’s Republic of China persistently seeks to define—when it comes to global perceptions.

The main point: Through top-down policy decisions and greater public participation, Taiwanese museums are increasingly working to present a more modern and diverse image of Taiwan. To showcase these efforts to the global community, they will need to work more closely with international partners—and current efforts in digitization are a great starting point.