Since the beginning of the Russia-Ukraine War, militaries around the world have been closely observing each stage of the conflict, learning operational lessons and beginning the process of adaptation. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA), of course, is not an outlier in this process. However, as a party army—the PLA is the armed branch of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP, 中國共產黨), rather than the national army of China—the PLA will also seek to adapt lessons to ensure the political demands of the CCP leadership are met. CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping (習近平) is well known to be a micromanager, subsuming many state roles into newly established party commissions that he directly leads.

In this case, though, Xi does not need to create new authorities to exercise military power: as chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC, 中央軍委委員會主席), he has long-established, immense powers to direct the PLA, all the way down to the operational and tactical levels. For instance, during the PLA response to then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, Xi reportedly directed the firing of ballistic missiles into Japan’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

Thus, PLA analysis will likely be filtered through the lens of Xi’s existing biases and priorities. Higher-level adaptive responses have a high possibility of being contorted, either by Xi himself or by leaders seeking to ingratiate themselves with Xi (i.e., the “working towards the Fuhrer” phenomenon). In this article, I will review some of the published analysis on potential PLA lessons learned from the war. I will then consider how this will likely be interpreted and prioritized given party direction. Finally, I will look at the implications of all of this for the future defense of Taiwan.

Lessons Do Not Equal Adaptation

In September 2022, Dr. Joel Wuthnow of the US National Defense University looked at some of the existing literature on potential PLA lessons in his article, “Rightsizing Chinese Military Lessons From Ukraine.” His analysis split the lessons into two categories: first, “Reinforcing Lessons,” which “confirm the value of previous PLA decisions;” and second, “Pivotal Lessons,” which “force the PLA to reconsider its assumptions or move into a new direction.”

Wuthnow was careful to mention that whether or not the PLA would actually learn from these lessons rested on three assumptions: (1) that PLA decision-makers are teachable; (2) that there is a rational strategic planning process; and (3) that adaptation will influence China’s decision-making calculus.

He also noted that, as of the time of publication, “the PLA has made it frustratingly difficult to answer these questions using direct evidence: several months into the conflict, PLA officers have produced almost nothing detailing their views on the implications of the conflict for future Chinese operations and modernization. It is also doubtful that internal assessments, if they exist, will be available in a way that can substantiate foreign speculation.”

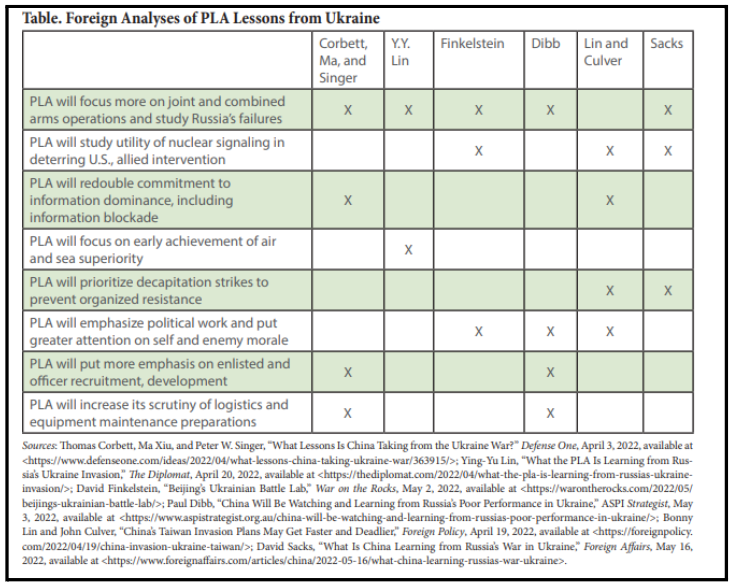

Thus, with these caveats in mind, Dr. Wuthnow summed up a number of lessons he had gathered from Western analysts, as summarized in the table below:

Image: Joel Wuthnow’s September 2022 summarization of Western open-source analysis of PLA lessons learned. His conclusion was that most of these lessons aligned with PLA assessments formed prior to the Russia-Ukraine War. (Source: US National Defense University)

Most of these lessons derive from well-documented Russian operational failures, with the notable exceptions of perceived advantageous use of Russian nuclear signaling and Ukrainian information warfare. However, it is important to note that lessons do not necessarily equate to adaptation. Even in the ideal scenario of an intellectually honest and creative military free from political influence, the military reform process requires prioritization. PLA resources are significant but not infinite, and there are lessons that will compete for resources.

An example of this is the “utility of nuclear signaling in deterring US [and] allied intervention,” something also considered by PRC analysts. Prior to the war, the PLA was already in the middle of an expansion of its nuclear stockpile: from 400 warheads in 2021 to an estimated 1000 warheads by 2030. This already represents a rapid increase in nuclear capability, with correspondingly higher supporting costs (such as hardened facilities/silos, security forces, and increasingly sophisticated delivery mechanisms).

Yet even this increase is grossly insufficient to credibly use nuclear weapons as a form of deterrence against conventional intervention. Both the United States and Russia have approximately 1700 deployed nuclear warheads, with thousands more in reserve. Moreover, the United States has had a complex nuclear deterrent approach since the 1960s, including the development of adaptive conventional-nuclear integration against the threat of exactly this sort of escalation-signaling, limited nuclear attack. In contrast, public PLA strategic doctrine has remained the same since the beginning of the PRC nuclear program, with a “no first use” policy. Thus, if the PLA were to directly adapt Russian nuclear signaling methods, the PLA would need to further exponentially increase their stockpile while diversifying into capabilities like low-yield nuclear weapons. Even more importantly, the PLA would need to completely redesign their nuclear doctrine, training, and concepts of risk management: threatening the use of nuclear weapons early in a crisis would be highly and unpredictably escalatory, going against the PLA concept of “war control” (戰爭控制) as a method of protecting the CCP. Finally, every yuan spent on this would mean one less yuan spent on improvements in conventional capability.

This is just one lesson that would be difficult for the PLA to directly adapt in a cost-effective way. PLA planners will instead likely selectively and indirectly adapt lessons, particularly in areas which have applications outside of pure warfighting and in areas that Xi Jinping has clearly prioritized. The increase in nuclear capability, for instance, is one of Xi’s priorities simply as a marker of the PRC’s status as a great power – even if it is unlikely to be credible as a nuclear deterrent against intervention. Instead, the PLA may seek to adapt these capabilities as part of a broader gray zone campaign to persuade its neighbors that accepting a PRC-led order would be less expensive and risky than a nuclear arms race or US regional nuclear deployment.

Xi as the Ultimate Teacher

As the nuclear example indicates, Xi has a longstanding vision of what the PLA should be as a “world class military” (世界一流軍隊), and the PLA will work to fit reforms within that vision. His exhortations to the PLA have remained remarkably consistent over his last decade of power: “ensure absolute loyalty of the troops” (確保部隊絕對忠誠), “dare to struggle” (敢於鬥爭, likely referencing internal resistance to reform), and “be able to fight and win” (能打榜、打勝榜).

Xi’s public remarks since the start of the Russia-Ukraine War, particularly during the October 2022 20th Party Congress and the March 2023 “Two Sessions,” have repeated those themes. To the extent that the Russia-Ukraine War may have influenced his public thinking and guidance, what hints we do have tend to indicate that the war has reinforced his existing concerns with the PLA. First, Xi mentioned in November 2022 the necessity of “consolidation and enhancement of integrated national strategic systems and capabilities” (鞏固提高一體化國家戰略體系和能力). This is likely a reference to information dominance and still greater military-civil fusion (軍民融合), to ensure that domestic PRC tech and the PLA can offset perceived US technological containment. The US and EU attempt to choke Russia off from microchips, which has led to Russian inability to scale up high-tech weapons and munitions production, has likely reinforced this.

Image: A Ukrainian soldier moving a Starlink satellite dish, January 2023. The Starlink constellation has been critical for Ukrainian military communication. This has provided Ukraine with strategic and operational benefits to situational awareness, targeting, morale, and communication to a global audience. Conversely, Russian inability to counter or replicate the thousands of highly distributed terminals has hampered their military operations. This feeds into existing PLA concerns on information dominance and capacity. (Image source: Reuters)

Second, the 20th Party Congress Work Report once again mentions the need to “win local wars” (打贏局部戰爭). This is something of a climb down from the more expansive 2019 vision of the roles and missions of the PLA, which highlight global power projection to “protect China’s overseas interests.” This re-prioritization speaks to continued and long-term party distrust in the ability of the PLA to be able to succeed in even a regional war, let alone a global struggle. Russian inability to rapidly win a war against a smaller nation on their own border, even while the Russians played up their ability to defeat NATO in a much larger war, has likely reinforced these fears.

These expectations provide an outline for the expected new military strategic guidance (軍事戰略方針), which was last updated in 2019. This hints at a “back to basics” doctrinal re-write: reviving the 2015-era doctrine of “winning informatized local wars,” while emphasizing capacity (both in personnel and logistics). Rather than adaptation influencing China’s decision-making calculus, it seems that the party center—that is, Xi—will influence adaptation.

Implications

Xi seems to have taken a low-imagination approach to lessons from the Russia-Ukraine war: “what we were already doing, but more.” A PRC focus on informational dominance and capacity will mean that Taiwan must consider similar countermeasures. Unlike Ukraine, Taiwan cannot depend on SpaceX’s Starlink: it is not available in Taiwan yet, and SpaceX’s CEO Elon Musk is vulnerable to PRC coercion given the scale of his other enterprises within the PRC. Moreover, Taiwan would not have access to all of Western Europe and American industry to build capacity while fighting a war.

Asymmetric concepts can offset some, but not all, of the imbalance. If the PRC is now preparing for the potential of a protracted conflict, Taiwan must take steps against this contingency as well.

The main point: The Russia-Ukraine war offers a number of lessons for the PLA. However, adaptation requires prioritization. Under Xi’s ever-tightening control, the PLA will prioritize Xi’s ideas—most of which seem to focus on re-doubling the PLA ability to fight a protracted war over Taiwan.