Undersea cables lie on the seabed deep beneath the waves, making it difficult to detect network sabotage until after the fact. It is therefore easy for foreign governments, such as the People’s Republic of China (PRC), to argue that one of their nations’ vessels causing the severance of an undersea cable is an accident. In a recent case, the perpetrator cited an ‘accident‘ as the reason for cutting an undersea cable around Taiwan for the fourth time this year. However, in a major shift regarding Taiwan’s national security, on June 12, a Chinese national—who was the captain of a Togolese-registered vessel, Hong Tai 58 (宏泰58)—was sentenced to prison by Taiwanese authorities for severing the Taiwan-Penghu No.3 cable. For the first time, the Taiwanese government has taken serious action to heavily penalize someone who was responsible for endangering Taiwan’s undersea cables—hardware that is now designated by Taiwan’s Ministry of Digital Affairs (MoDA, 數位發展部) as “critical infrastructure.”

Image: Taiwan’s Coast Guard Administration escorts the Togolese vessel suspected of dragging an anchor across the Taiwan-Penghu No. 3 cable back to Anping Port for investigation (February 25, 2025). (Image Source: Taiwan’s Coast Guard Administration)

Undersea cables are cables laid deep along the ocean floor carrying internet and telecommunications traffic across large stretches of the ocean. Without them, there would be no global internet connectivity allowing people to make video calls and send text messages at a moment’s notice. On average, 150 to 200 undersea cables around the world are damaged each year, usually as a consequence of natural disasters such as earthquakes or fishing accidents. Taiwan is connected to 14 international undersea cables and 10 domestic cables. Additionally, Taiwan has experienced several major cable-cutting incidents over the past several years. In 2025 alone, there have already been four recorded cable cuts: two due to natural causes and two due to suspected sabotage from Chinese vessels.These include the severance of the Trans-Pacific Express, Taiwan Matsu No. 2, and Taiwan Matsu No. 3 cables.

In response to these incidents, Taiwan has installed mitigation measures, such as microwave backup systems—a wireless alternative for reliable data transmission after a cable has been cut. While such developments are positive, the Taiwanese government knows that true communications resiliency will require a plan B that is stronger than microwave backup systems. Unfortunately, microwave backup systems come with their own set of problems: such as unclear lines of sight, which result in obstruction through ground terrain and interference from radio signals. In the case of a major contingency such as an invasion or blockade of the Taiwan Strait, the PRC is likely to engage in sabotage and cut some—if not all—of Taiwan’s undersea cables, throwing the nation’s government, military, and general population into digital darkness. Satellites are the only alternative to ensure Taiwan is not cut off from the rest of the world.

Satellites and the New Space Race

As the 21st century space race has taken off, satellites have become vitally important. Despite the fact that satellite connectivity only accounts for one percent of all internet traffic, governments and private companies around the world are racing to launch satellites, particularly low-earth orbit (LEO) satellites. While Space X’s impressive Starlink constellation of nearly 8,000 satellites spearheads the space frontier, Taiwan is developing its own version of Starlink, due to disputes with SpaceX over Taiwan’s ownership laws, and national security concerns. Taiwan’s “National Space Technology Long-term Development Program,” the third phase of a government initiative established since 1991, is advancing the nation’s indigenous satellites. In the 2019, the Executive Yuan (EY, 行政院) approved the current phase of this program, spanning until 2028, with a budget of NTD 25.1 billion (USD 848.6 million). Moreover, the EY intends to further extend the program’s timeline to 2031 and inject an additional budget of NTD 40 billion (USD 1.4 billion) into the program.

Satellites and Lessons from the Russia-Ukraine War

The Russia-Ukraine war serves as a case study for how the Taiwanese government can better prepare its communications resilience during a conflict. The day before Russia invaded Ukraine, one of the first decisive attacks included a cyber attack on the Viasat KA-SAT network–knocking thousands of people off the internet, and illustrating how communications infrastructure are at immediate risk of attack during war time. Starlink, the world’s largest satellite constellation, provided free Starlink connection to allow Ukraine access to its terminals. Connecting to the internet via Starlink, Ukrainian troops were able to communicate quickly and effectively, guiding drones to exact target locations with the ability to quickly reassess and pinpoint enemy locations. While Russian troops were able to disrupt traditional communication networks, Starlink enabled the Ukrainian military to have access to reliable internet connectivity.

Compared to Ukraine, one of Taiwan’s biggest disadvantages is its terrain. Starlink satellites use Ku or Ka-band frequencies which support higher rates of data. However, they also experience more atmospheric interference. In an interview with Karina Wugang, a researcher from the Institute of the Study of War, she shared that: “One ideally needs a clear line of sight to the sky to get a good signal. Tall buildings, trees, and mountains will affect connectivity, and Taiwan has all three. It’s important to be cognizant that Taiwan’s geography is not as ideal as Ukraine, which has mostly flat and open fields.” [1] A constellation sufficient for Taiwan’s communications resilience would require at least 120 satellites, a far cry from the six LEO-satellites that Taiwan currently plans for launch by 2029.

What About Anti-Satellite Weapons?

Despite China’s demonstration of its ability to destroy satellites via anti-satellite weapons (ASAT), due to limited territorial space in space and the destructive nature of direct attacks on satellites, governments and private companies are less likely to engage in actions that escalate wartime conflict in the space domain. There are two types of ASATs: destructive ASATs, which are objects or weapons that can physically crash or destroy satellites, and non-destructive ASATs, which include objects that are conducted from regular air space, ground stations, and low orbit and can disable satellites without collision. Governments are more likely to engage in less escalatory tactics using non-destructive ASATs such as jamming satellites, which broadcast radio frequency signals to overpower satellite signals or engage in cyber attacks. Most countries have yet to demonstrate ASAT capabilities—with the exception of the United States, Russia, China, and India—and there has never been a war in which participants have employed ASATs. The United States is also spearheading a multilateral initiative to ban destructive ASAT testing in space, an effort that is gaining support from multiple governments and private aerospace companies. In a set of Taiwan invasion scenario wargames conducted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), both the United States and China refrained from engaging in satellite warfare due to the high risk of mutual communication failures.

Taiwan’s Domestic Satellite Communications Program

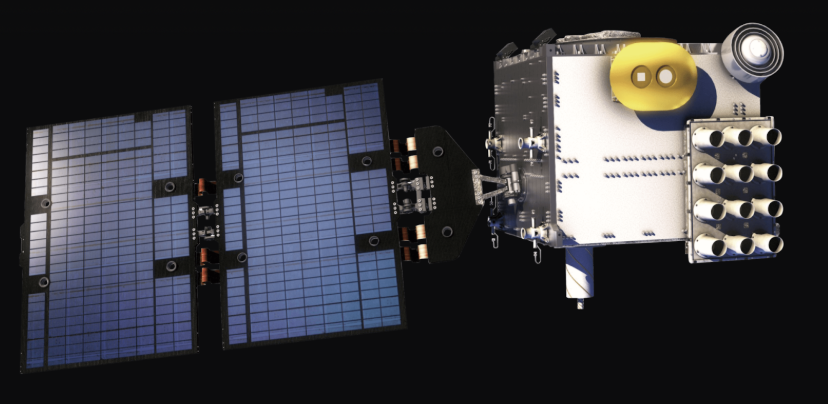

Unlike Ukraine, Taiwan’s greatest current advantage is time. In line with the PRC’s “One China Principle,” the PRC has continuously articulated a clear intention to “reunify” with what it believes is the breakaway province of Taiwan, by force if necessary. According to the US Central Intelligence Agency, China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA, 人民解放軍) is preparing to be ready for an invasion of Taiwan by 2027. As a result, the Taiwan Space Agency (TASA, 國家太空中心)—which is overseen by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC, 國家科學及技術委員會)—is spearheading the “Beyond 5G LEO Satellite Program,” a public-private partnership project with Taiwanese telecom companies to help develop six LEO satellites for Taiwan’s domestic satellite communications system by 2029. The project plans to launch six LEO satellites that will offer a communications system similar to Starlink. The first two satellites (1A and 1B), which are designed to test and verify two-way communications between the satellites and ground stations, will be deployed and launched by 2026. The project also includes the development of Taiwan’s own launch rockets and launch pads.

Image: Taiwan Space Agency’s image of the FORMOSAT-7 remote sensing satellites. (Image Source: Taiwan Space Agency)

Besides the planned LEO satellites, Taiwan’s FORMOSAT-5 and FORMOSAT-7 remote sensing satellites currently support international and domestic disaster relief, as well as meteorology. Taiwan plans to expand these capacities by launching FORMOSAT-8 optical sensing satellites starting in October of this year, as well as FORMOSAT-9 synthetic aperture radar (SAR) satellites between 2027-2029. SAR satellites can make observations during the day and night time, regardless of weather. These satellites will include edge computing capabilities, which reduces latency and the bandwidth necessary for processing data in real-time. Essentially, SAR satellites can support Taiwan’s defense posture in real-time battlefield intelligence to support military decision-making.

Taiwan’s Foreign Partnerships

Thus far, Taiwan is partnering with three major foreign satellite providers to enhance its communications resiliency. Taiwan’s first commercial license for a LEO satellite, provided by the United Kingdom’s Eutelsat Oneweb, has been approved and will be serviced by Chunghwa Telecom (Taiwan’s leading telecommunications service provider). Taiwan has inked an additional deal with Luxembourg’s SES to provide medium earth orbit (MEO) satellites. Finally, Chunghwa Telecom has signed a contract with the US-based company Astranis to purchase a microGEO satellite—a smaller, more flexible, and less expensive version of geostationary satellites. The microGEO satellite launch is expected by the end of 2025, with bandwidth capability available by 2026. The Taiwanese government, via the NSTC, is also in talks with Amazon’s Kuiper, which has approval by the US Federal Communications Commission to launch 3,200 LEO satellites. Additionally, half of those satellites must be launched by July 2026. As of this year, Kuiper has currently launched 27 LEO satellites. If Kuiper can meet the July 2026 deadline to deploy half of its LEO satellites, a partnership with Amazon’s Kuiper would significantly enhance Taiwan’s efforts to fortify its communications resilience.

If projections are accurate and the PRC has the military readiness to invade Taiwan by 2027, Taiwan has less than two years to solidify its communications priorities. This is imperative, given that the Executive Yuan has reportedly instructed the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP, 國家科學技術委員科技辦公室) to write up a strategy for multiple government agencies to coordinate on Taiwan’s satellite communications. Despite this, there has only been one such relevant meeting as of October 2024. [2] Taiwan is investing in strategies to enhance its communications resilience by fortifying its undersea cables, undersea cable backup systems and LEO satellites. This includes partnering with foreign satellite providers and developing its own domestic satellite system; however, this takes time and resources, making deals with existing satellite networks like OneWeb and Kuiper critical in the interim.

Policy Recommendations:

In order to expedite Taiwan’s satellite program, the author suggests the following policies:

- Taiwan should continue to encourage partnerships with a diverse range of foreign-based communications and aerospace companies to provide Taiwan with payload capability, while Taiwan continues to build its own domestic components, such as radio frequency parts and power amplifiers.

- Taiwan should continue leveraging its own technology in the space industry supply chain, including semiconductors and its advancements in information and communications technology (ICT). Companies interested in developing products in a microgravity environment, which are impossible to make on earth, are already meeting in Taiwan. Rupert Hammond-Chambers, president of the US-Taiwan Business Council emphasized that “Taiwan is in a position to replace some Chinese suppliers in the supply chain as US companies are trying to root out Chinese sourced sub systems.” [3]

- The Executive Yuan should provide the OSTP, the government agency in charge of creating a strategic plan for Taiwan’s satellite communications at the inter-agency level, a deadline to submit its strategy. The EY should also mandate monthly or quarterly meetings to ensure cooperation between all government agencies involved in Taiwan’s satellite domain, including the National Communications Commission (NCC, 國家通訊傳播委員會), MoDA, TASA, and the Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA, 經濟部).

- In its efforts to collaborate with non Starlink satellite companies, the Taiwanese government must prioritize negotiations with foreign companies that could grant Taiwan access to a large fleet of LEO satellites such as Amazon’s Project Kuiper and Eutelsat’s Oneweb for communications resilience–especially in the event of a military conflict across the Strait.

The main point: The PRC has continuously engaged in the probable sabotage of Taiwan’s undersea cables, undermining Taiwan’s national security and sovereignty. In order to counteract the probable severance of Taiwan’s undersea cables by the PRC in the event of an invasion, Taipei has invested in satellite communications, which will play a crucial role in defensive military operations. However, there is still much that needs to be done.

[1] Author’s interview with Institute for the Study of War’s China Researcher Karina Wugang, June 5, 2025.

[2] Internal memo from the BowerGroup Asia, June 13, 2025.

[3] Author’s interview with US-Taiwan Business Council President, Rupert Hammond-Chambers, June 30, 2025.