In July this year, a Taiwanese court handed down a criminal conviction for the destruction of an undersea communications cable. The Chinese captain of the Hong Tai 58 (宏泰58號), a bulk carrier, was sentenced to three years in prison after his vessel loitered in February in a government-designated no-anchor zone (禁錨警戒區) and severed a critical submarine cable between Taiwan and Penghu. The incident caused over NTD 17 million (USD 520,000) in damages to Chunghwa Telecom (中華電信) and temporarily disrupted vital civil and government communications. Although the defendant claimed negligence rather than malice, the court found him guilty of gross dereliction of duty. The ruling marks not just a judicial milestone but a strategic one. Undersea cables are no longer mere commercial assets—rather, they are infrastructure representing Taiwan’s sovereignty.

Taiwan is beginning to see gestures of support from its partners. In Washington, a bipartisan duo—Senators John Curtis (R-UT) and Jacky Rosen (D-NV)—has introduced the Taiwan Undersea Cable Resilience Initiative Act. The bill calls for the US State Department to lead a cross-agency effort to counter threats to Taiwan’s undersea cables—including support from the Pentagon, Department of Homeland Security, and the US Coast Guard. The law would require the US government to assist Taiwan in boosting its monitoring architecture, building early-warning systems, launching joint patrols with Taiwan’s coast guard, and—should sabotage occur—imposing Magnitsky-style sanctions on People’s Republic of China (PRC) actors.

Whether or not the bill passes in the US Congress, the Taiwanese government must establish its own resilience mechanisms to thwart PRC attacks on its undersea cables. These mechanisms must span three critical domains: the rule of law, multi-domain monitoring, and repair capacity. Without those pillars, any external support may be undermined by internal frailty.

The Rule of Law

Taiwan has made some institutional strides in its recent legislation related to undersea cable security. In mid-2023, after a string of suspicious cable breaks near the Matsu Islands of Taiwan, the Legislative Yuan (立法院)—controlled by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP, 民進黨)—rushed to amend the Telecommunications Management Act (電信管理法), making intentional damage to undersea infrastructure a punishable crime. The deterrent was promising, but short-lived. PRC vessels were suspected of causing two additional breaks in the first two months of 2025. As with many other issues in Taiwan’s national security toolkit, legal whack-a-mole is no match for systematic prevention.

In this, Australia and New Zealand offer blueprints. Since the 1990s, these two countries have introduced “submarine cable protection zones”—government-designated maritime corridors where anchoring, dredging, bottom trawling, and other high-risk activities are banned. One Australian protection zone near Perth spans 60 nautical miles and plunges to a depth of 2,000 meters. The rules are enforceable, and violations carry legal and financial penalties. This model not only codifies deterrence, but it also shares responsibilities between the state and private operators—a hallmark of resilient infrastructure governance.

By contrast, Taiwan has yet to establish a formal legal framework for submarine cable protection zones. While certain maritime areas are monitored through Chunghwa Telecom’s Submarine Cable Automatic Warning System (SAWS, 自動示警系統) and patrolled by Taiwan’s Coast Guard Administration (海巡署), these zones currently lack binding legal restrictions on potentially deceptive activities. To help close the gap, the Executive Yuan (行政院) has approved draft amendments this September that would require vessels navigating through Taiwan’s territorial sea to keep their Automatic Identification System (AIS)—a technology through which ships communicate— switched on and transmitting accurate information, with the bill now under deliberation by the Legislative Yuan. Even with this progress, Taiwan should consider adopting the Australia/New Zealand model for restricting certain maritime activity, like trawling and anchoring, in protected areas.

Undersea cables are as vital as high-voltage power grids to Taiwan’s resilience. Their protection should not stem from ad hoc responses alone, but must be backed by enforceable legal obligations and penalties. In recognition of this, legislators from the ruling DPP—including Chen Kuan-Ting (陳冠廷), Chang Hung-Lu (張宏陸), and Su Chiao-Hui (蘇巧慧)—have held interagency meetings with the Ministry of Transportation (交通部), the Ministry of Digital Affairs (數位發展部), and the Ministry of the Interior (內政部) to explore the feasibility of creating such zones. [1]

Multi-Domain Monitoring

When it comes to monitoring threats to its undersea cables, Taiwan possesses a handful of technological tools but still lacks systems that can provide breadth of vision and real-time responsiveness. Chunghwa Telecom’s aforementioned SAWS can detect vessels over 20 meters in length traveling at speeds below 5 knots when they enter within one kilometer of a submarine cable route. It automatically transmits warning messages to the ship’s bridge, advising quick passage and instructing them not to loiter or anchor. Yet, its effectiveness depends heavily on the AIS and is of limited use when vessels transponder or operate without notification.

In order to gain the upper-hand in real-time monitoring, Taiwan must scale up its intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities. This includes advancing indigenous satellite development, most notably the synthetic aperture radar (SAR)-equipped FORMOSAT-9 program (福衛九號). Two FORMOSAT-9 satellites are scheduled for launch in 2028 and 2030. These satellites are expected to support persistent land and maritime surveillance, and if deployed in sufficient numbers, could even detect covert intrusions, such as rubber boats approaching Taiwan’s coastline.

Simultaneously, Taiwan should leverage high-frequency commercial satellite imagery from providers like Planet Labs and Maxar, integrate geospatial data with intelligence partners such as the United States and Japan, and deploy AI-enabled anomaly detection tools. Together, these approaches would allow Taiwan to identify suspicious loitering patterns near critical infrastructure, such as undersea cable junctions, and build a real-time awareness chain that extends from early warning to prosecutable evidence.

Command of information has never been solely about data possession. Data possession must be paired with the ability to act swiftly and credibly in ways that alter an adversary’s strategic calculus. Taiwan needs to build a response protocol that turns monitoring data into evidence, and evidence into deterrence.

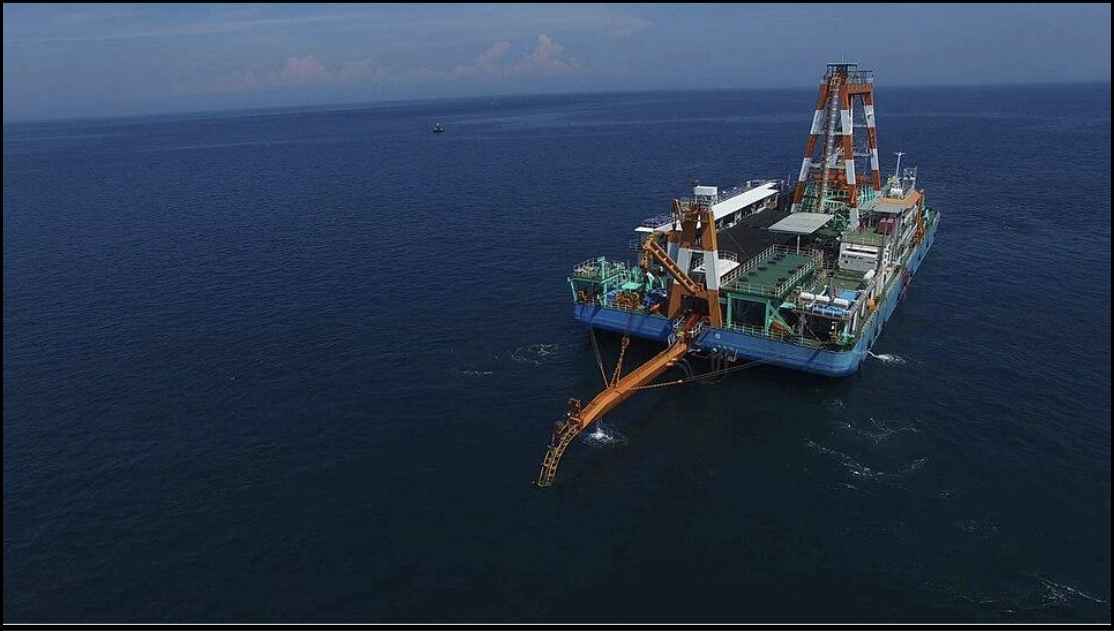

Image: The construction of the Taiwan-Penghu submarine cable. (Image source: Taipower/Wikimedia Commons)

Repair Capacity

The final layer of Taiwan’s cable protection is physical resilience. Cable repair is no longer a logistical afterthought, but rather a strategic asset. Taiwan is a member of two regional cable maintenance zones (YOKOHAMA and SEAIOCMA), which offer six vessels that could theoretically serve Taiwan’s repair needs. However, none of them are Taiwan-owned. Worse, global capacity is aging. According to the International Cable Protection Committee, which Taiwan rejoined this year under the name of Chinese Taipei, the world’s 48 cable ships are, on average, nearly 30 years old. If sabotage becomes routine, relying on third-party dispatch is a strategic liability.

Rather than passively waiting for assistance in times of crisis, Taiwan should take the initiative by proposing a regional, multi-role cable repair ship program, jointly developed with the United States and Japan and designed for dual civilian and military use. In peacetime, such a vessel could be commercially operated and maintained. During contingencies, it could serve as a platform for restoring strategic communications and defending critical infrastructure. This would demonstrate Taiwan’s role as a responsible stakeholder and contributor to Indo-Pacific security.

The main point: Each PRC cable sabotage incident is more than a disruption. It is a test of Taiwan’s resilience. Taiwan must make sabotage costly, predictable, and futile. That requires law, sensors, and ships all working in concert. Undersea cables are vulnerable. Taiwan must not be.

[1] These meetings were not open to the public and therefore have not been reported by the media.