Introduction

Seeing the neighborhood toughen up for the worst, the Philippines has made huge leaps to secure its strategic interests. Under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., Manila has set its house in order to realize those interests. Manila’s security policy evolution requires consolidation of its archipelagic and maritime geography to uphold its sovereignty and to demonstrate agency in the region.

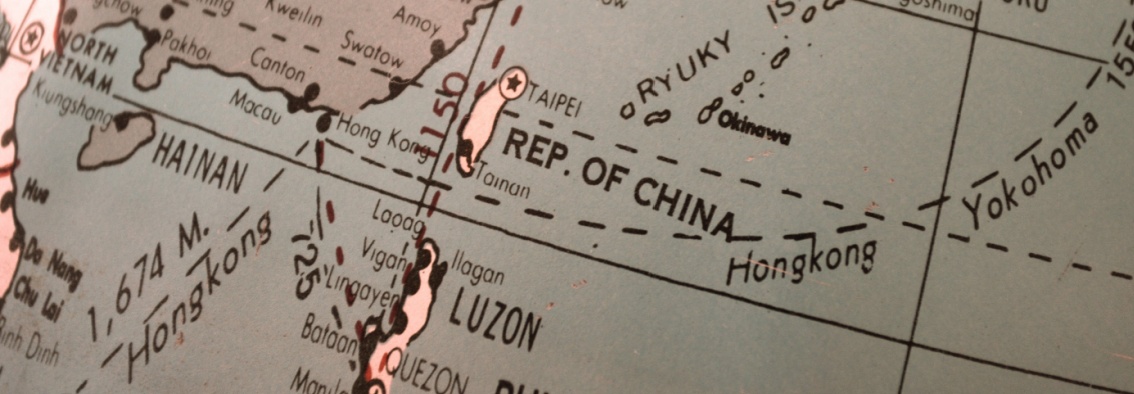

The Philippines has made notable efforts in the West Philippine Sea (WPS)—its claimed portion in the South China Sea (SCS)—to offset the People’s Republic of China (PRC)’s maritime expansion, with initiatives such as the Transparency Initiative and Multilateral Maritime Cooperative Activity. Meanwhile, there is another frontier that deserves equal attention—the Luzon Strait, which is neatly adjacent to the Taiwan Strait. Some view the WPS and the Luzon Strait as distinct frontiers and would therefore advise a policy of restraint against entanglement with cross-Strait issues. Nonetheless, the Philippines has its own strategic logic for taking action.

This article intends to unpack this strategic logic and how it will shape the decisions of all stakeholders. It argues that Manila sees the WPS and Luzon-Taiwan straits as interlinked frontiers, and that the world should view this quiet development as the unfolding of a “New Cross-Strait Security Complex.” It may not necessarily result in the Philippines abandoning its One-China Policy—nor is it calling everybody to “abandon ship” in doubling down efforts to the WPS—but stakeholders can no longer ignore this emerging dynamic and must recalibrate their approach.

The Strategic Logic

In a separate Global Taiwan Brief article from 2023, this author contended that Manila’s National Security Policy 2023-2028 (NSP) demonstrates Manila’s evolving strategic calculus toward Taipei, potentially opening a window of opportunity for expanded Philippine-Taiwan ties. Since 2023, we have observed a rather mixed picture of saber-rattling by Beijing—warning Manila “not to play with fire” in what it views as meddling in Chinese domestic issues—and political signaling by Taipei, which hinted that regional players like Manila could leverage the island-nation’s New Southbound Policy for economic gains despite limited formal relations.

Even without personally meeting each other, Philippine and Taiwanese leaders have recently been exchanging good graces. For instance, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. congratulated President Lai Ching-te (賴清德) on X (formerly Twitter) on his electoral victory as the island-nation’s president in January 2024. In just April this year, President Marcos Jr. eased long-standing restrictions on Philippine officials—except for the president, vice president, and secretaries of defense and foreign affairs—that prevented them from visiting Taiwan to expand bilateral trade and investment. In August, the Philippine President expressed concerns that the Philippines’ geographic proximity to the Taiwan Strait would require his country to become involved in a conflict between Beijing and Taipei. Perhaps for this reason, Taiwan’s Vice President Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) told the press on the sidelines of an international forum in November this year that Taiwan and the Philippines must strengthen cooperation—to tackle not only economic issues, but also security challenges that beset the region. As one Democratic Progressive Party (DPP, 民進黨) legislator has said, the two nations have “started to smile at each other.”

While the Philippines and Taiwan maintain an existing coast guard cooperation agreement that followed a deadly maritime crisis back in 2013, a Japan Times report recently uncovered that Manila is quietly deepening its defense ties with Taipei. Although details remain unclear, the media has already picked up signals, such as Taiwan’s informal participation in the Philippine-hosted Balikatan Exercises’ International Observer Program (featuring 19 nations total). A Taipei Times article reported that Taiwanese military observers joined the Kamandag Exercises, a drill for Philippine, American, and Japanese marines held in Batanes this year.

For what its worth, the Philippine NSP states that Manila cares about the cross-Strait relations between Taiwan and PRC—a consequence of its interlinked concerns on trade, remittance, protection of overseas Filipinos, and the potential influx of humanitarian refugees from the island-nation. Some may dismiss such concerns as merely reactive, but the document offers a national security vision of “a free, resilient, peaceful, and prosperous archipelagic and maritime nation, at peace with itself and its neighbors, enabled by reliable defense and public safety systems.”

So far, the operational grammar to express this strategic logic has been to repeatedly wargame a Taiwan contingency. In its 40th iteration of the Balikatan Exercise this year, the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), with its American, Australian, and Japanese counterparts, rehearsed several combined arms functions—most notably, a drill in the islands of Batanes (Manila’s northernmost province near Taiwan). Thanks to the expansion of agreed-upon locations in Northern Luzon through which American faces can rotate—following a renegotiation of the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement in early 2023—basing, logistics, joint fires, and command-and-control, among others, are becoming much less of a problem for the AFP and its likeminded counterparts.

Public sources indicate that Manila guides its strategic community to enact the country’s defense logic through the Comprehensive Archipelagic Defense Concept (CADC). Militarily, the AFP translates CADC’s operational grammar through the Comprehensive Archipelagic Defense Operations (CADO), by providing force management to the AFP Northern Luzon Command (NOLCOM)—the unified command in charge of defending the areas proximate to Taiwan. Here, Manila fixes its gaze at Mavulis Island, the northernmost island in Batanes, which practically stands at the Luzon-Taiwan Straits frontier. As the lone AFP NOLCOM outpost, Mavulis Island has become a lightning rod for security discourse on the mixed picture of symbolism and substance.

On the American side, US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth informed the public before a March 2025 joint conference with Philippine Defense Secretary Gilberto Teodoro about an planned bilateral special force training operation in Batanes. While this announcement signals a silent nod from the Philippine side, the AFP leadership is also contemplating how the AFP NOLCOM and Western Command (WESCOM)—one that is in charge of defending the Kalayaan (Spratly) Islands and maritime features in the WPS—can learn, plan, and operate with each other in an event of a full-scale war, where they would expect the PRC to prove a serious foe.

A New Cross-Strait Security Complex?

Hard times call for recognizing the emergence of the New Cross-Strait Security Complex, a subregional security complex emerging in this important part of the Indo-Pacific region. While some might view this merely as an academic term, increasing institutional, material, and cognitive patterns of interaction are already in place. [1]

Several wargames conducted by think tanks, like the Center for Strategic and International Studies and the Center for New American Security, highlight that Manila is no longer merely a bystander in regional security. It is now asserting the Philippines’ agency through its status as a local actor to burnish its legitimacy in carving out a distinctive pattern of interaction affecting national and regional security.

The world must notice this pattern of WPS and Luzon-Taiwan Straits interlinkage not because of the Philippines’ narrow national interests, but because of what Manila’s modest efforts contribute to an emergent subregional security complex.

The New Cross-Strait Security Complex does not imply interference into PRC and Taiwan’s respective domestic affairs. For instance, the Philippines understands this sensitivity and would not risk its people’s safety and throw away economic benefits in favor of excessive friction with the PRC. It must be said that the Philippines’ regional motives are modest, if not complacent—as compared to PRC’s goals to foster a defensive seawall in the First Island Chain that involves Taiwan as its underbelly. Yet, this same regional interdependence with Beijing and Taipei prompts Manila to carve new ways of thinking about and seeing its neighborhood.

With all this in mind, it must be said that Manila lacks resource capacity, and it constrained in its policy autonomy to navigate the new security complex. At the institutional level, pressures from the opposition remain—such as when President Marcos Jr.’s sister, Senator Imee Marcos, who then chaired the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, pressed Foreign Affairs Secretary Maria Theresa Lazaro in August this year to clarify President Marcos’ statement on the Taiwan contingency. Secretary Lazaro hurriedly reiterated the One-China Policy. Senator Erwin Tulfo disagreed, remarking that respecting the One-China Policy does not translate into a solution for the PRC’s actions in the WPS. Secretary Lazaro rebutted by deferring to existing de-escalatory mechanisms with Beijing.

At the societal level, recent public opinion polls show that most Filipinos are in strong support of the Philippine government’s efforts in the WPS. However, there is yet to be solid evidence regarding public approval for Manila’s Taiwan contingency activities. In fact, the public responded with a mixture of uproar and anxiety when the AFP announced that it was training to “fight on its own” for up to 30 days if a conflict occurs. Pundits remark that holding the line until relief comes from the US and allied forces will be a challenge for maintaining trust, yet even so, the same polls show high support for Manila to cooperate with America and other counterparts.

So, while societal and institutional challenges are present, the Philippines continues to muddle through and sometimes create opportunities that make subregional security complexes emergent.

Conclusion

This article is in no way prescribing immediate fixes to the PRC’s revisionist behavior. As regional players convene to consider fostering a “one-theater” concept against the PRC, the emergent New Cross-Strait Security Complex warrants attention for those who care about the regional commons. Practically, modest cognitive changes must take place, such as recognizing the role of the Philippines not only in the WPS, but also in the Luzon-Taiwan Strait frontier—not so that Manila can be dragged into a conflict, but so that it can co-create opportunities along defense, economic, and developmental lines.

The Luzon Economic Corridor is one of the great starting points, but stakeholders must pitch more intensified and inclusive models to scaffold the New Cross-Strait Security Complex into a formal regional hub. Informal talks over smart harbors between Manila and Taipei within the said corridor are also a welcome development to provide nuance beyond the domineering microchip discourse. Wargaming centers can initiate this cognitive shift from the bottom up, which should ripple into Track 1.5/2 dialogues. Ultimately, the Philippines’ strategic logic reminds us that collective deterrence works alongside diplomacy and development—especially across the New Cross-Strait Security Complex that it now shares quietly with Taiwan.

The main point: External observers often view the West Philippine Sea and Luzon-Taiwan Straits as distinct strategic areas and may well advise Manila to keep to that thinking. From the Philippine perspective, however, these frontiers are interlinked and are testing the country’s capacity. The world must grasp this strategic logic and the emergence of a “New Cross-Strait Security Complex”—which is germane not only to Taiwan’s future, but also the fate of the regional commons.

[1] The author conceptualized the “New cross-Strait Security Complex” based on Barry Buzan and Ole Wæver’s Regional Security Complex and Leonardo Bandarra’s Hierarchy Complexes of (re)ordering the periphery—particularly the material, institutional, and cognitive structures that underpin the interaction of actors. See Barry Buzan and Ole Wæver, Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003); and Leonardo Bandarra, “(Re-)Ordering from the Periphery: Hierarchy Complexes and Agency in the Global Nuclear Order,” Cambridge Review of International Affairs (2025), https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2025.2461630.