Foreign companies—including Taiwanese companies—seeking to invest in the United States have a new hurdle to face as legislation moves forward to enhance government oversight. This will pose a problem for those who embrace the same methods they have used to navigate Washington for years. Understanding and especially overcoming the hurdles will be important, even more so for companies domiciled in certain countries. Senator John Cornyn (R-TX) and Representative Robert Pittenger (R-NC) have led the reform effort with their respective introductions of the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2017 (FIRRMA) in early November. All indications are that the legislation’s prospects are enhanced by consultations between Congress and the Administration that occurred as it was being drafted.

Indeed, Congress and the Trump Administration appear to be in alignment about the need to reform the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), the inter-agency panel run by the Treasury Department, which assesses potential foreign investments in the United States for their national security implications. Ostensibly a voluntary review, companies that fail to seek approval from CFIUS and are later found to have risks in their transactions can be sanctioned, hit with expensive mitigation costs, or even forced to unwind the investment post-transaction. Washington fears that aggressive state-sponsored efforts by companies in certain “countries of special concern” are harming US national security interests in ways that current legislation does not enable CFIUS to address. The two countries of most concern are China and Russia—with Taiwan viewed as an extension of China’s threat. Efforts to reform CFIUS—the first since 2008—are moving forward with bipartisan support.

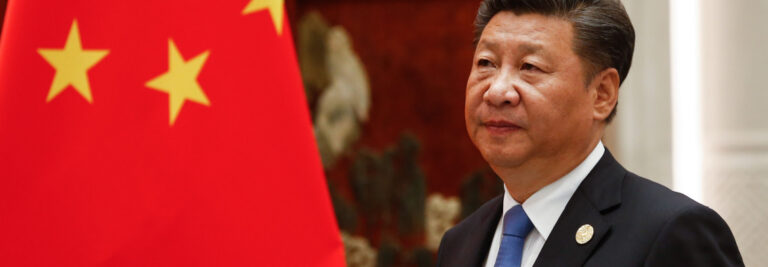

With President Trump’s roll-out of the National Security Strategy, there should be no confusion that China is viewed as a competitor by this White House. There should also not be anyone who does not understand that America’s view of national security is heavily focused on economic strength—both at home and abroad.

So what implication does this have for Taiwan? First, the context is crucial: there are mixed sentiments about China in Washington. Some are focused on China as a broad market and potential strategic partner. Others view intellectual property infringement, state-sponsored hacking, denial of market access, and regional maritime expansion as indicators that China is more a competitor than a friend. While there are of course substantive differences between China and Taiwan that earn Taiwan favorable consideration by pro-democracy advocates in Congress, there is also a belief that Taiwan’s economic dependency with China—with many of its major companies with significant exposure in the People’s Republic of China (PRC)—could mean that Taiwanese investment in the United States may be considered a presumed proxy for the Chinese government.

Part of what is driving CFIUS reform is the increase in cases that have transacted in recent years. In 2009, CFIUS reviewed only 65 cases. In 2015, that number had risen to 143. Attorneys who handle CFIUS matters expect the 2017 tally to exceed 200 cases and perhaps crest higher than 240. At the same time, there is no statutory definition of “national security” so recent cases have focused far beyond the simple acquisition of a semiconductor manufacturer that also sells to the US military.

There are heightened concerns now regarding transactions that expose to foreign parties the Personally Identifiable Information (PII) of American citizens—which might include healthcare companies, social media, financial clearinghouses, especially if those foreign companies have inadequate cybersecurity safeguards—and others that might give a foreign entity proximate access to sensitive US government facilities. Transactions related to key technology sectors—including robotics and artificial intelligence—are also routinely cited by CFIUS staff as areas of concern.

If passed as it is currently written, FIRRMA will have important implications for Taiwanese investments. The legislation establishes that unnamed “countries of special concern” can be scrutinized more aggressively in CFIUS reviews while “identified countries” meeting certain criteria would earn exemptions or more expedited reviews. It extends the review and investigation time that CFIUS can require before rendering a judgment. Among other things, it also broadens the Committee’s jurisdiction to include real estate lease transactions, minority investments, licensing deals, technology sharing arrangements, and outbound investments that have implications for US equities. It also establishes a mandatory review for any foreign acquisition of 25 percent or more in equity of a US company by a company that is 25 percent or more owned by a foreign government—which could mean state investment entities and parastatals.

While not explicitly stated in the legislation, Taiwanese companies that have joint ventures with mainland Chinese firms will be an area of concern. Joint ventures are of concern because of the risk of technology leakage they pose. The same applies to licensing deals and transactions that will expose US intellectual property via the supply chain of the foreign acquirer.

With all of this in motion, there is good news for companies that are serious about their investment strategy in the United States: CFIUS is not in place to stop foreign investments, only to defray the negative effects for US national security. That means that a foreign company can work with the new system by understanding the legitimate concerns of CFIUS and taking proactive measures to mitigate the risk. These measures include everything from utilizing the established legal proxy structures that many attorneys favor to instituting robust auditing regimes by reputable and non-conflicted firms. However, this approach also includes innovative and aggressive counterintelligence risk management, involving everything from network surveillance and segmentation, to physical separation of employees and facilities, to the employment of cutting-edge sensors and rapid reaction capabilities. The most important factor for CFIUS approval is whether the proposed transaction adequately addresses the risk concerns of CFIUS staff. If the risks are not mitigated, CFIUS has no basis for approving the transaction.

The reform legislation will make CFIUS a more robust means of protecting US national security interests. Importantly, the negotiated legislation remains focused on national security despite the interest of some in including US trade equities and reciprocal market access. While this legislation resolves some open questions about the role of CFIUS, this is still a relatively opaque regulatory process. Efforts to circumvent, game, or politicize the process are unlikely to be successful or to be received well by those charged with making judgments. CFIUS, which already has all the tools it needs to decline most types of transactions, is now being given more enhanced tools. Regardless, the strongest tool CFIUS has remains the private conversation that a specific transaction is “not going to happen” between CFIUS and the attorneys representing the transaction parties.

The main point: Because of perceptions about the relationship between Chinese and Taiwanese businesses, CFIUS reform could make it harder for Taiwanese companies to engage in a broad range of transactions involving American firms and technology, but there are numerous proven risk mitigation approaches that can be used to meet CFIUS requirements. The biggest mistake a company can make is to ignore the staff concerns or try to politicize the process.