In April 2023, Quanta Computer (廣達電腦)—a Taiwanese electronics maker and top manufacturer for Apple MacBooks—solidified an agreement with a plant in Vietnam to begin production “as soon as possible.” iPhone assembler Foxconn (also known as Hon Hai Precision Industry, 鴻海精密工業股份有限公司) has also invested heavily in the northern region of Vietnam, with estimates that 30 percent of its production will be done outside of China by 2025. Such moves are part of a larger trend of Taiwanese companies looking to diversify production away from China, especially at a time of rising labor costs, tense geopolitical circumstances, and heightened supply chain risks. Yet, this shift has thus far not been coupled with an interest in returning these industries to Taiwan—instead, these manufacturers are moving to regions with limited regulations, favorable taxation environments, and low-cost labor.

The history of Taiwanese companies, or Taiwanese-owned companies, in China is a long and complex one. Entrepreneurs from Taiwan (also known as tai shang, 臺商) initially moved production capacity to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in pursuit of lower operating costs following the end of Taiwan’s martial law period. Prior to China’s economic boom, these industries had a significant impact on the business environment in China. Taiwanese entrepreneurs not only brought along the capital and innovation necessary to spur economic growth, but also the systems, know-how, and practices along with it. [1] Since then, however, operating in China as a Taiwanese company has become more financially costly and risky.

Taiwanese Workers and Businesses Begin to Look Beyond China

It is not just tech companies that have plans in motion to expand operations beyond China. For instance, Pou Chen Group (寶成工業股份有限公司)—a producer for shoe brands such as Nike and Adidas—has ramped up production in India, while production in China now represents only 10-20 percent of its output. Overall, new investments in China by Taiwanese companies are down, declining by over 10 percent year-on-year in the first quarter of 2023. This trend is also not unique to Taiwanese companies, as South Korea’s Samsung, the United States’ Hasbro, and Sweden’s Volvo have all made the move to relocate or expand production outside of China.

While some analyses indicate that these companies are leaving China entirely, there are indications that many companies are not necessarily removing parts of the supply chain from China, but are instead adding or expanding operations elsewhere. During a GTI panel on Taiwan’s economic security, the Center for International Private Enterprise’s (CIPE) Catherine Tai highlighted that risk mitigation at the firm level for Taiwanese companies focuses on the diversification of the supply chain, rather than wholesale relocation.

In this context, several key drivers of this shift have been identified. While US-China competition has long been a concern for Taiwanese companies, former President Donald Trump’s trade war with China increased economic tensions between the two substantially. In addition to this volatile business environment, companies also faced rising costs for inputs, including labor and electricity. These challenges were further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, during which China’s zero-COVID policy forced companies and individuals to navigate substantial logistical and financial barriers. According to a survey conducted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in 2022, over 70 percent of Taiwanese companies stated that Taiwan needed to reduce its economic dependence on China, citing risks posed by a potential US-China conflict, cross-Strait conflict, and China’s zero-COVID policy.

Additionally, while such cases are usually not officially reported, instances of political intimidation of Taiwanese entrepreneurs by PRC officials have also contributed to heightened risks of operations in China. Even as research has shown that tai shang tend to remain non-political while conducting business in China, authorities have threatened and fined businesses or groups they deem to be “pro-independence,” or of having political ties to Taiwan’s Democratic Progressive Party (DPP, 民進黨). Taiwanese businesspeople are often subject to frequent questioning by local officials—euphemized as “having tea”—regardless of political affiliation (or lack thereof).

Alongside these shifts, the number of Taiwanese citizens working in China has also dropped steadily since 2014. While there were once concerns that China’s enticement of Taiwanese talent and labor was contributing to—or at least benefitting from—Taiwan’s “brain drain,” data seems to indicate that labor flows are leaning toward Southeast Asia instead. While the causes of this transition have not been fully surveyed, there are several reasons why this is unsurprising. Of course, the number of Taiwanese working abroad correlates with Taiwanese companies based abroad. As these companies move operations, their labor forces must follow suit. Additionally, Taiwan’s government has put forth several policies in recent years that may have guided talent flows away from China: such as banning staffing companies from posting China-based job openings in Taiwan, and increasing investment in Southeast Asia as part of the New Southbound Policy (NSP, 新南向政策).

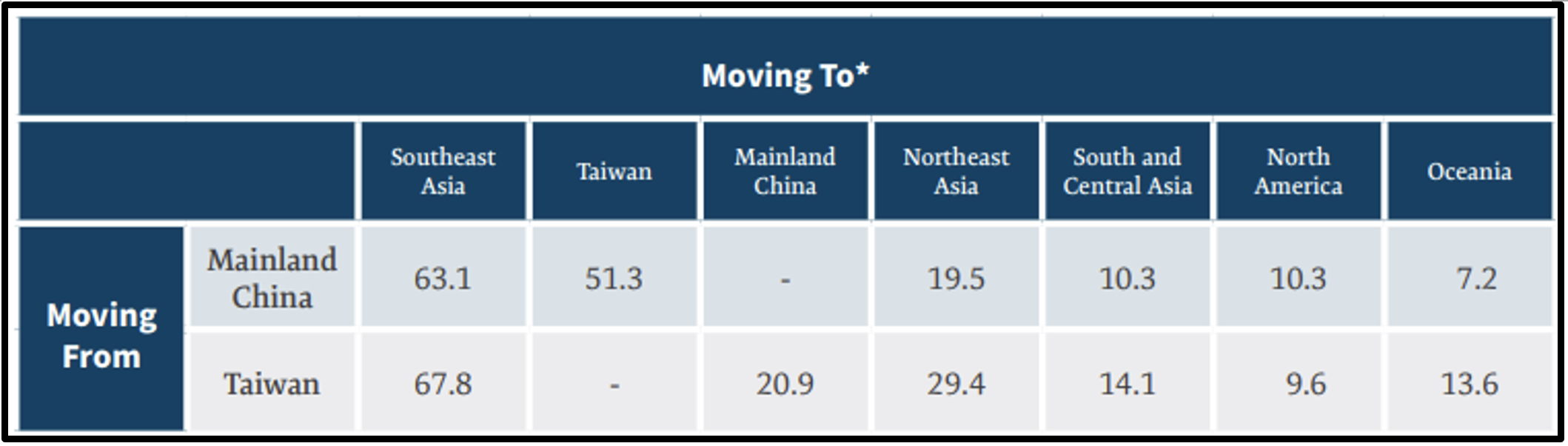

Indeed, shifting labor flows to Southeast Asia has been paralleled by an expansion of Taiwanese companies’ operations in the region. In fact, the CSIS 2022 survey indicated that over 63 percent of Taiwanese businesses leaving China were relocating production to Southeast Asia. Rather than reshoring—that is, returning operations and productions to the country of origin—Taiwanese companies have fully embraced “friendshoring.” In this case, Taiwan’s “friendly countries” in Southeast Asia may not refer to a strong sense of allyship in the region, but rather a low-risk, low-cost environment for fruitful business operations. Additionally, as mentioned by Catherine Tai, “TSMC [Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, 台灣積體電路製造股份有限公司] and other companies cannot move alone—they need the whole cluster to move with them.” For Taiwanese companies, Southeast Asia offers a more predictable political environment and can accommodate entire manufacturing ecosystems.

Graphic: The majority of Taiwanese companies in China and Taiwan looking to move production elsewhere favor Southeast Asia as a new destination. (Graphic source: CSIS)

Moving Out, But Not Always Moving On

While Taiwanese business expansion beyond China has been widespread, it has not been simple. Corporations with a long history in China have established comprehensive networks with local authorities and other businesses, have access to key manufacturing infrastructure, and have developed well-organized supply chains. As such, the transition from China to Southeast Asia has required significant commitment and investment.

In addition to these complications, Taiwanese enterprises face new challenges in expanding operations into other regions. Southeast Asian states such as Vietnam, Thailand, and Singapore each come with their own set of regulations, which require Taiwanese businesses to seek new certifications and permissions, as well as adapt to new taxation systems. While not a new issue, companies expanding abroad must also adjust to new work culture environments, which has not always been an easy barrier to overcome. Despite its fabrication plant in Arizona being relatively new, Taiwan’s TSMC has already received 91 reviews on its Glassdoor page—less than one third of which recommend employment with the company. Comments cite TSMC’s “brutal” work culture and long hours, which have long been considered standard and necessary practices in the company’s Taiwan branches.

At the same time, not all Taiwanese business leaders have been on board with lessening economic engagement with China—at least not at the macro level. In May 2023, Matthew Miau (苗豐強), the head of the Chinese National Federation of Industries (CNFI, 中華民國全國工業總會)—one of the largest and most influential business groups in Taiwan—issued a statement urging Taiwanese companies to continue engagement with China. Both trade and investment, he argued, are key to “maintain[ing] cross-Strait peace.” While the security implications of economic engagement between Taiwan and China are beyond the scope of this discussion, the practical and logistical barriers to disengagement are legitimate concerns.

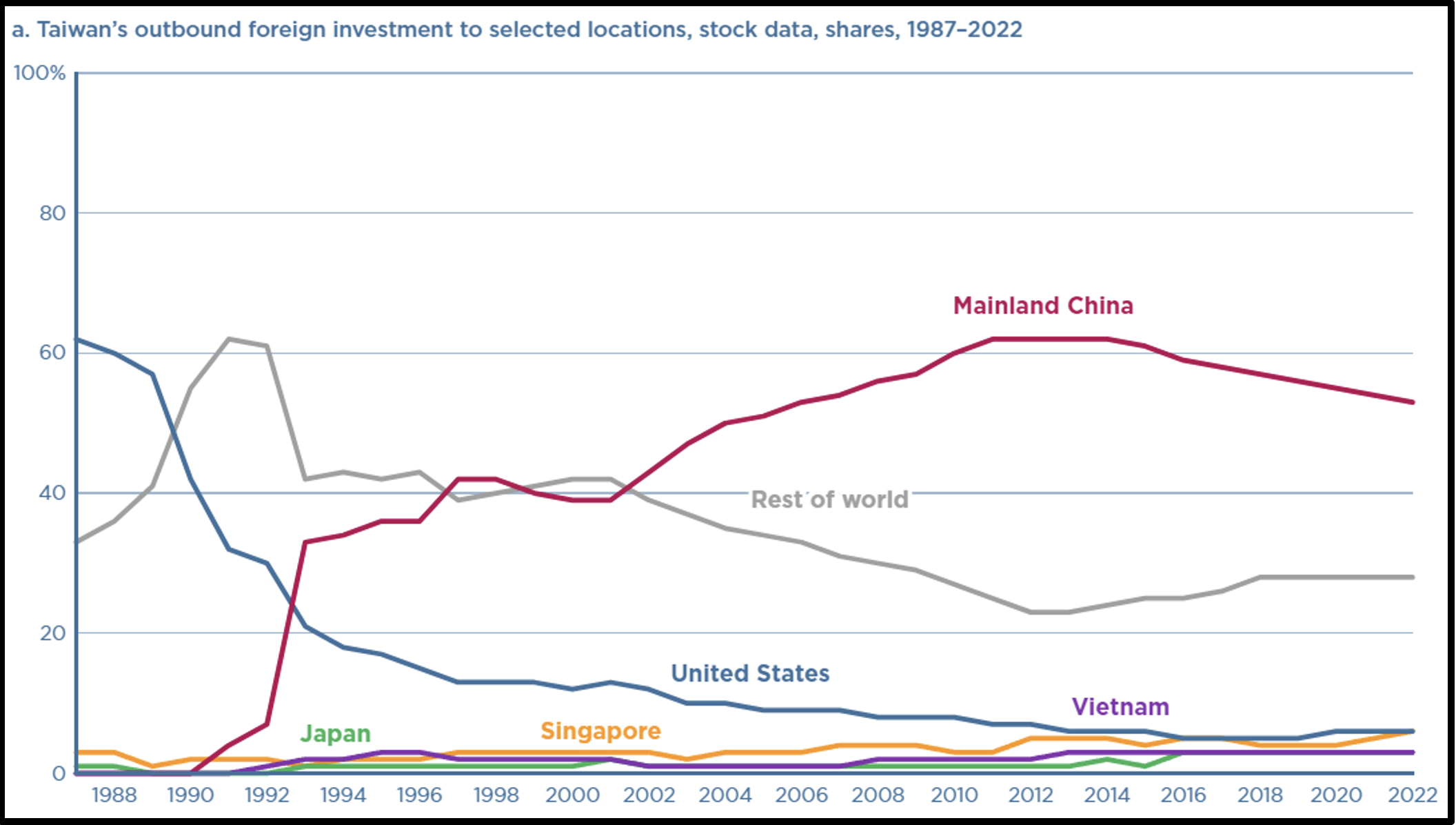

Indeed, data still indicates that the majority of Taiwan’s outbound foreign investment—specifically in the field of technology—still largely goes to China. While industries such as textiles have seen a decline, and overall investment seems to have stalled, other regions have yet to surpass China as an investment destination. This slow transition cannot necessarily be attributed to Taiwan’s interest in Southeast Asia as a “recent development,” as businesses have been looking to Southeast Asia for as long as they have to China.

Graphic: Despite incentives and controls, Taiwan’s foreign investment in China still surpasses all other destinations. (Graphic source: Peterson Institute for International Economics)

The Future of Investment in Taiwan

As mentioned previously, an exodus of Taiwanese businesses from China has not necessarily been coupled with a return to Taiwan. In fact, around 33 percent of Taiwan-based companies surveyed indicated that they have already moved or are considering moving from the island, with the majority moving to Southeast Asia. Taiwanese companies reshoring to Taiwan from China is also not a new concept, as businesspeople have argued since 2012 that Taiwan’s educated workforce and stable political environment make it a viable alternative for industrial development. But with the logistical barriers discussed above, and ongoing concerns regarding Taiwan’s national security—which can undermine investor confidence in the country—the Taiwanese government has a substantial challenge ahead to encourage reshoring.

In a crucial first step, the Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA, 經濟部) launched the “Invest Taiwan” initiative in 2019, which has an action plan to specifically target overseas Taiwanese businesses: a plan they estimate has attracted over NTD $1 trillion (roughly USD $32 billion) in investment. Beyond incentives for overseas Taiwanese companies, also addressed by the initiative, Taiwan still lacks key structures in place to support inbound foreign investment. As candidly noted by Crossroads Founder David Chang, Taiwan’s business environment still poses key barriers to international investors, some of which are ingrained in Taiwanese society: complex and unforgiving banking systems, language and cultural barriers, and arduous immigration policies have stood in the way of Taiwan’s path to becoming an investment destination for foreign companies. To attract more foreign investment—especially in the face of Taiwan’s aging population—Taiwan will first need to address these foundational issues.

As the competition between the United States and China continues to manifest itself in the fields of economics and business, and costs in China continue to rise, Taiwanese companies and businesspeople will likely continue to seek destinations for business development elsewhere. For Taiwan, positioning itself as a destination for reshoring or inbound investment may be key in maintaining its economic growth. Of course, it is difficult to compete with the low-cost, low-risk environment offered by Southeast Asian states. In this context, Taiwan must think creatively about the role its companies play in its own economic strength.

The main point: While Taiwanese companies look to diversify production away from China, this shift has not been coupled with an interest in returning these industries to Taiwan, but rather to regions with limited regulations, favorable taxation environments, and low-cost labor.

[1] Shelley Rigger, The Tiger Leading the Dragon: How Taiwan’ Propelled China’s Economic Rise (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021).